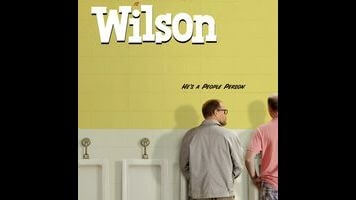

Woody Harrelson softens Daniel Clowes’ misanthropic Wilson for the big screen

The cartoonist Daniel Clowes has built a career on misfits, misanthropes, and losers—society’s black sheep in black-rimmed glasses. But among his gallery of downtrodden outcasts, Wilson stands out for the sheer exasperating force of his personality. Introduced in the pages of the 2010 graphic novel that bears his name, Wilson is a bespectacled, middle-aged divorcée with no social graces, no self-awareness, no filter between brain and motor mouth. He’s the kind of asshole who sits down next to complete strangers on a bus or in a café, ignoring every empty seat in the vicinity, and begins breathlessly coughing up conversation, asking invasive personal questions and then scoffing at the reluctant answers he receives. He’s the kind of asshole who confuses rudeness for lacerating honesty, anti-conformist platitudes for wisdom. He’s the kind of asshole you don’t make eye contact with in public (or at the family reunion). Exasperating doesn’t quite do him justice, to be honest.

It’s a gamble, building a comedy around a character this boorish. Who, after all, wants to spend an hour and a half in the company of someone they’d avoid like the plague in real life? But Wilson, the new movie based on Clowes’ comic, has an ace up its sleeve, and it goes by the name of Woody Harrelson. His face framed by scraggly gray tufts, his eyes darting behind frames, the actor pretty closely resembles the various versions of Wilson that Clowes sketched on paper—and he talks like the character, too, spewing verbal diarrhea straight from the comic. But Harrelson, with his goofball stoner energy, can’t help but bring a certain gregarious charm to the role, even when, say, casually insulting a date or shouting obscenities at people on the street. Without shying away from the fundamental obnoxiousness of this bull in the social china shop, Harrelson softens him somehow. For a prick, his Wilson is almost likable.

Superficially speaking, the movie doesn’t deviate much from its source material. Clowes himself wrote the screenplay, just as he did for two previous comedies based on his work, Ghost World and the underrated Art School Confidential. The book version of Wilson was structured as a series of one-page gag strips, which helps explain why the movie often plays like a punchline machine, dropping Harrelson into various situations/encounters and then cutting away on a caustic remark. A plot gradually takes shape around these cringe-worthy episodes: Following the death of his father, Wilson goes searching for the ex-wife who left him decades earlier and finds not the rundown “crack whore” he’s been describing to anyone who will listen, but the mostly put-together Pippi (Laura Dern, expertly playing foil to this maddening windbag). What’s more, he learns that Pippi didn’t abort the child she was pregnant with when they split, but put her up for adoption instead—meaning that Wilson, much to his unexpected delight, has a teenager daughter (Isabella Amara).

That makes Wilson, in theory and in panel form, a meditation on midlife anxiety—a tragicomedy about a loud-and-proud outsider who suddenly realizes that he wants the traditional family life he’s heretofore dodged. There’s a good chance it might play that way on screen, too, had Terry Zwigoff, who directed those other Clowes adaptations, also made this one. (Ghost World, especially, established the filmmaker as a perfect fit for the author’s potent blend of deadpan humor and middle-class melancholia.) Instead, Wilson has been shepherded by Craig Johnson, director of the Sundance-approved sibling dramedy The Skeleton Twins, and he can’t quite manage the tone: This Wilson mashes Clowes’ acid wit and existential despair into a more sitcomish shape, transforming the bad behavior of its eponymous anti-hero into quirky shtick. Can a film be both bitterly misanthropic and kind of cuddly? Johnson achieves that dubious distinction, even as he pushes Wilson from misfortune to misfortune, the years stacking up on his shoulders.

Clowes plays his part, too. No amount of vulgarity can disguise the gently charitable redemption arc his screenplay follows; like any number of American indies anchored by ostensibly insufferable protagonists, this one can’t quite resist extending a sympathetic olive branch. Maybe everyone involved would have been better off not hedging their bets and just letting Wilson (and Wilson) be as exasperating as possible. In making the character’s assholery almost agreeable, Harrelson is technically complicit in sanding down the project’s rough edges. But he’s also responsible, almost in presence alone, for its spare moments of poignancy, because there’s something strangely affecting about seeing the actor, now 55, play an aging dope trying to make sense of his life. Plus, he’s really funny, delivering each off-color joke and uncomfortably tactless observation with a true-believer’s zeal. Clowes fans may be vaguely disappointed with Wilson. Harrelson fans will not be.