Wu-Tang affiliates like Sunz Of Man and Killarmy started spiraling out of control, diluting the stamp of quality that the infamous yellow “W” represented. By 2000, it’d almost mean nothing; Ghostface’s Supreme Clientele was formed out of its rubble, a postmodern playground of syntax. The Wu would reassemble for more group efforts of varying levels of quality and corporate intrigue in the ensuing years, but the drums never snapped quite like they did on Forever, the synthesizers and samples never felt quite so radioactive, the rapping never so venomously, fiercely competitive. They never again collectively hit highs like “Little Ghetto Boys” or “Cash Still Rules” or “Impossible” or “The Projects.” And they never had another video like “Triumph.”

“Triumph” was the first single on the record, a 5:22 stretch of razor-tipped darts shot from a crew that seemed set on bum-rushing the throne room, remaking hip-hop’s monarchy as a nine-man oligarchy. The track was released in Feburary ’97, five months after Tupac was shot to death and a month before The Notorious B.I.G. would be. The path to the throne was paved with shiny suits: Biggie was still bouncing jubilantly on his yacht, as far as radio and MTV were concerned. Puff was tap-dancing through airports in his memory. Will Smith shimmied up to a new era of swear-free minivan rap. Hip-hop was coalescing with pop, moving out of the purity of its golden age of pure emceeing and tight David Axelrod loops in favor of crossover appeal, crooned hooks, Ja Rule, “rap and bullshit.” In ’96 Jay-Z was sampling Nas and Tribe on Reasonable Doubt; in ’97 he was duetting with Blackstreet. It was Clinton’s second term, and everyone was ready to make money.

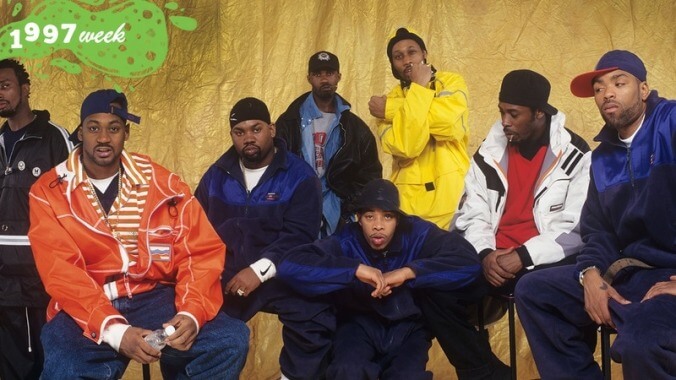

In its early videos, the Wu appeared as the consummate early ’90s rap crew, spitting over flaming barrels beneath overpasses and malingering in graffiti-strewn stairwells. Even on “Da Mystery Of Chessboxin’,” the action cuts between men literally doing kung fu on a chessboard and decrepit industrial settings full of iron bars and rusty structures. But to go big, as rap in ’97 dictated, Wu didn’t go clean, nor did it go shiny. It got weirder. “Triumph” seems beamed in from some alternate universe, where selling out meant hiring Brett Ratner to weave together a string of the worst special effects ever devised by man into a six-minute tableau of gonzo superhero mythology. The group spent almost a million dollars on it and went weeks over schedule. As Raekwon aptly told MTV in a contemporary making-of featurette, “It’s like if a little kid were to picture it, it would be like a big hype magazine, like a comic book or whatever, with the bangingness in it, though.”

“Triumph” begins on a rooftop, with Ol’ Dirty Bastard—or, rather, a man pretending to be Ol’ Dirty Bastard, seeing as he’d bailed from the set out of apparent disinterest—drawing the attention of onlookers, police, and journalists. Check out behind ODB, as he promises to rub your ass in the moonshine, the clouds billowing like plumes of taupe smoke; through the flames the whole crew comes spiraling. Inspectah Deck spits his first verse pretending to be Spider-Man; he sprints downward, catches a suicidal ODB, and they both turn into bees that then turn into Method Man, who lives out his Johnny Blaze fantasies as a flaming biker. (“I get to ride the bikes,” Method Man told MTV at the time. “That’s all I’m there to do, is ride the bikes.”)

Cappadonna appears in some sort of underground lair, slept on even in the conceptual stages of this music video. U-God, by point of comparison, gets to rap from a flaming Mortal Kombat hellscape full of other, smaller U-Gods, alongside archival footage of atomic bomb detonations.

RZA, ever committed to his own gonzo concepts, is the only one who shows up dressed as an actual bee for his verse, eventually turning into more computer-generated bees before we hit what is, for my money, the video’s climax, in which the GZA appears as some sort of god, a grown-up starchild who speaks in rhyming couplets.

Masta Killa is so wise, his verse helps a blind man see. Ghost and Rae spit from a strobe-lit bank vault (?), at once exempt from all this comic-book shit and utterly enthralled by it. We do not talk enough about the fact that Ghostface plants a tender, fraternal kiss on Raekwon at the end of this video, perhaps because the previous six minutes has already provided enough brain fodder for a couple decades.

It has taken me all that time, for example, to realize that the golden coliseum in which the crew appears together is actually the interior of a beehive. It scans here more as a sort of Thunderdome, with the group rapping from a pillar rising out of an abyss.

The tower image pops up throughout the video—Ol’ Dirty and Masta Killa both rap from on high, and it closes with a New York skyline—which is an apt image for the scale the video hoped to achieve. But the Thunderdome is appropriate, too, given the troubles the RZA had holding the group together to make Wu-Tang Forever, not to mention the ensuing decades of rivalries and breakups and barely squashed beefs.

The RZA’s initial promise to the rest of the Wu-Tang was that if they gave him five years of service, he’d turn them all into stars. It’s why so many of the city’s best rappers were willing to subsume their identities into the greater collective—this idea that their collective firepower was strong enough to maintain interest through a gradual reveal. Part of the joy of listening to early Wu-Tang records is their overwhelming myopia, functioning as self-contained universes crafted around each rapper. With hindsight, we know that those identities were too large, those ambitions bigger than RZA’s grimy aesthetic could contain. ODB would flame out. Ghost would go supernova. Method Man would go Hollywood. RZA would also go Hollywood, but worse. Raekwon and GZA would keep honing their crafts, reliably and inventively.

But the Wu-Tang Clan was, itself, just as myopic. When it declared “Triumph” in 1997 it wasn’t over the rest of hip-hop, reeling from senseless deaths and a sudden convergence with glossy mainstream pop. It declared triumph over the audacity of the Wu-Tang idea. Ever competitive, they were each declaring triumph over each other. It’s combustible music—self-evident proof of why Wu-Tang couldn’t last forever and, simultaneously, why it has.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.