WWI melodrama The Guardians strays from its valuable vision of life on the home front

A World War I movie that never goes near the battlefield (apart from one shot of corpses at the outset), The Guardians seeks to memorialize the hardships of those who stayed home. That means it’s primarily a story about women—in this case, French women who worked the family farm while their husbands, brothers, and fathers were being killed in the trenches. This invaluable shift in perspective seems like an ideal fit for director Xavier Beauvois, whose best-known previous film, Of Gods And Men, focuses on Islamic terrorism as it was experienced by a group of Trappist monks. Unfortunately, Beauvois adapted The Guardians from a novel published in 1924, and the book’s author, Ernest Pérochon, doesn’t appear to have had any ideas about women’s lives that don’t involve sexual infidelity and jealousy. What starts out as a testament to female fortitude, reminding us that sacrifices were also made on the home front, gradually turns into high-toned soap opera. Men remain mostly off screen, yet they drive the action all the same.

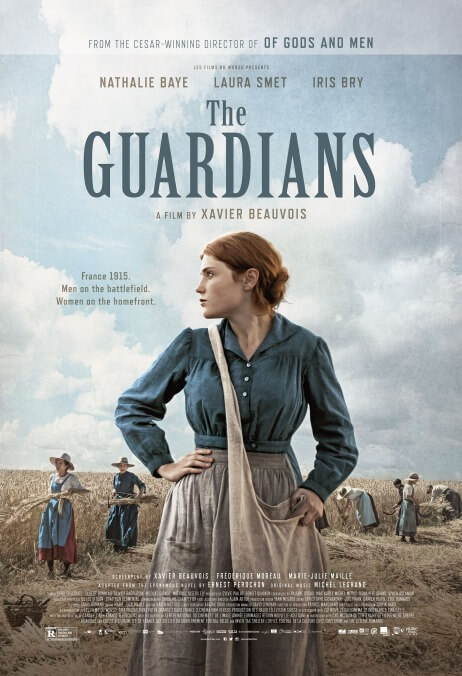

Spanning roughly four years, the film opens in 1915, as matriarch Hortense Sandrail (Nathalie Baye) seeks help for the annual harvest. With all able-bodied men away fighting, her sole recourse is to hire a young maid, Francine (Iris Bry), who quickly proves herself a hard worker and is soon adopted as an honorary member of the family. When Hortense’s youngest son, Georges (Cyril Descours), arrives home on leave, however, he and Francine fall in love; this greatly displeases Marguerite (Mathilde Viseux), a local girl who’s grown up with Georges and assumed that they would eventually marry. Worse still, rumors start flying that Hortense’s daughter-in-law, Solange (Laura Smet), whose husband is taken prisoner by the Germans halfway through the movie, has been sleeping around with some Americans who regularly buy the farm’s produce and sometimes work there as day laborers.

The Guardians is strongest during its lazily paced first hour, which Beauvois devotes largely to the details of farm life as it existed early in the 20th century. (It’s a huge deal when the family purchases a mechanized tractor toward the end of the film.) Bry, in her very first onscreen role, makes a compellingly rugged protagonist, and her quiet watchfulness plays well opposite Baye’s slightly imperious maternal warmth and Smet’s open yearning. Once the melodrama kicks in, though, there’s precious little to recommend. Events repeatedly hinge on Three’s Company-style misunderstandings (minus the comedy) of what characters briefly glimpse, and Beauvois loses sight of what the movie is ostensibly about—at one point, even serving up a hoary dream sequence in which Georges imagines himself knifing a German soldier to death, only to remove the enemy’s gas mask and discover his own face staring glassily back at him. (That was arguably already a cliché when it happened to Luke Skywalker in The Empire Strikes Back.) The film’s ending pays homage to Paths Of Glory, creating an alternate version of Kubrick’s offbeat coda, but that only serves as a reminder of the war’s horrific toll on soldiers. The Guardians seeks to provide another oft-neglected angle on wartime loss, but it never quite manages to conceive of its main characters as anything but subsidiary.