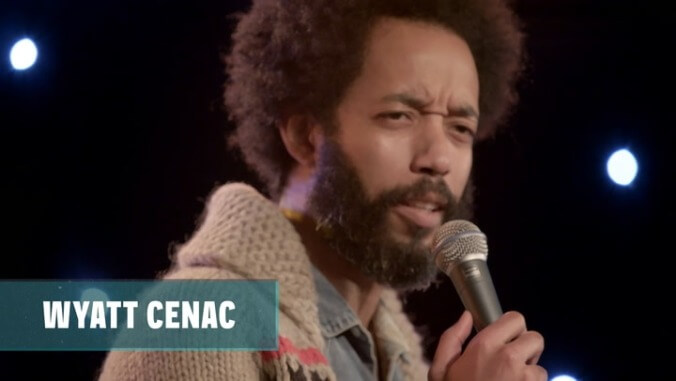

Wyatt Cenac on what makes him laugh, from Muppets to the most insane TV pilot of the ’80s

Wyatt Cenac first came to widespread public attention as a correspondent on The Daily Show. However, the comedian worked as a writer on King Of The Hill for several years prior to that, and had been performing stand-up comedy for years. Cenac has a new show called Night Train on comedy platform Seeso, which he both executive produces and stars in. Based on a long-running Brooklyn stage show, he plays host to a rotating and diverse collection of comedians performing live stand-up.

The A.V. Club recently spoke with him regarding one of our favorite subjects to talk about with comedians: What makes them laugh? Cenac came up with an idiosyncratic list, and was happy to delve into the arcane and sometimes random reasons why these things tickled him so much—especially when it came to one of the strangest TV pilots of the ’80s. We were almost as surprised to find ourselves talking with him at the very non-showbiz-friendly hour of 9 a.m.—his choice, not ours.

The A.V. Club: It’s very rare to get a comedian that wants to talk shop before, say, noon.

Wyatt Cenac: I like to think that I’m on Australian time. So there, I believe, it’s much later.

AVC: Speaking of being on international time, the last time I saw you perform live was at a show in Brooklyn, where you had just gotten back from England, and your entire set was about how depressed you were for the past week.

WC: Yeah, I think that was at the Bell House. I had just gotten off the plane. I think I threw some brownies into the crowd, because I had just bought some brownies, and I didn’t want to shame-eat them by myself. London and Paris, two wonderful places where I had a terrible time.

AVC: It was one of the most memorable performances I’ve ever seen. You seemed to be beaten down by life at that point.

WC: [Laughs.] That happens a lot.

The Grand Budapest Hotel

AVC: You’re not exactly alone in being a big fan of this one.

WC: I think it’s just a very beautiful movie. It’s a funny movie, but visually, it’s such an engaging film, not just from a standpoint of set design and shot selection, but even just the movement. There’s a moment when everyone’s punching everyone in the face, and it’s just such a silly, comedic moment, just the way they’re getting punched and falling and they’re all kind of doing it in the same way. Just those little details, those are really fun and when you see it once, when a person kind of drops like a Muppet, and then everyone else kind of follows suit. It just feels like a lot of attention was paid to that.

I recently started watching the films of Jacques Tati, and there’s a similar sort of attention to detail. I don’t know if Wes Anderson is a fan of Tati, or was influenced at all, but when you see Playtime, the use of the space and the expanse of the space is something that he does a lot in his films, and movement in that space. I think there’s something really nice about it. I feel like you could watch Grand Budapest without sound and it would still be funny.

AVC: That comparison makes sense. It’s almost like a Martian who took notes on human behavior and tried to represent it on screen, where everybody has a similar, weird way of behaving that is just universal throughout the film.

WC: Yes. And in its own weird way, winds up being a comment of its own. And I think that’s why if you look at Tati’s films, Playtime, and Mon Oncle, and Trafic, there’s a very similar looking at patterns. In those films, there’s very little dialogue. They just visually play in these ways—even just watching a person go up the stairs, and you think, “Oh okay, now they’re getting to their house,” and they go up another flight of stairs, and it’s all just one shot, finding the visual humor in things. The film takes its time so you can see those things happen.

To a certain degree, when we watch a lot of movies now, everything has to happen very quickly, and you can’t stay on a shot for too long, especially if you’re thinking larger budget films. Things have to keep moving. What’s nice about a lot of Wes Anderson’s films is that there’s a patience to it. I think that patience brings out a lot more funny things that you would miss otherwise if you just had to make quick cuts and keep the pace, whatever that pace is that bigger budget comedies have to have.

AVC: Do you tend to be a Wes Anderson die-hard? Or do you go back and forth on his stuff?

WC: I like a lot of his stuff. I think I’ve seen every one of his films. I like them all. I enjoy Life Aquatic. I think that one, from a visual standpoint, is just such a fun, visual movie to look at, whether it’s the shots of the ship cut down the middle, that set where you can see everyone in each of their rooms doing whatever and moving about—something like that, I could watch that on a loop for an hour. To me, that’s what’s so interesting, and when you can choreograph all that stuff properly, and you have again, just that attention to detail that each of these rooms has to have something visually interesting happening in it. All that stuff, it feels like a certain level of craftsmanship that you don’t get to have in a lot of other films.

The Muppets, “Stand By Me”

AVC: Speaking of craftsmanship, this Muppets short is great. Were you watching this season? Is that how you discovered this?

WC: No, this was something they were doing before they had the TV show, and I think before the Jason Segel movie. This was stuff they were doing on their own, they started a YouTube page, and I think the first thing they did was “Bohemian Rhapsody.” And then, they were just making these things on the side with no real other intention than to put them on YouTube, as far as I know.

There’s a very silly one with Beaker where Beaker is doing something online—I think he’s singing a song—and the internet comments come up, and people are just like, “This guy sucks, he’s terrible.” He’s playing guitar and there’s candles around, and something catches on fire, and all the internet comments turn into, “Oh my gosh, this guy is so funny,” and “Oh, he got burned.” It was this very weird comment on the anonymous online comment culture, but with Beaker. I just remember seeing these and thinking, “Hell yeah, this is what the Muppet show ought to be, just these. These are great.” This felt like just such a great line back to the old series.

But also looking at the one that I picked, “Stand By Me,” it’s silly, it’s weirdly dark, but at the same time, there’s kind of a happy ending to it, which is what the Muppets always felt like to me. There’s a lot of silliness, but there’s some sadness underneath it all, some darkness, and then there’s this resolution that, you know, you can still find joy in it. Just from the beginning, when that giant beast comes out, “I’m a bunny!” That gets me every time. It’s just so stupid. It’s so ridiculous. For it to keep going to the place where he’s just eating rabbits, and yeah, in your mind, like, I don’t think that’s made for a 4-year-old. There are enough people in the world who would say, “No, you can’t show a 4-year-old some monster eating a bunny, because they’ll get upset that he’s killed the bunny.”

But then the sort of reveal is that they’re just sort of singing in his stomach, and we’re taking the laws of science out of this, and it’s just this ridiculous, silly thing, and these characters aren’t real. So you can eat a bunny, and then the bunny can sing in your stomach, and we won’t deal with how you’re going to pass that bunny later.

And I think again, going to that idea of craftsmanship and attention to detail, the movement of all of the bunnies and the artistry of just having a puppeteer with a singing bunny, and then another puppeteer that is taking that bunny and swallowing it… there is a speed to which that puppeteer that’s got the bunny has to drop their hand, but also not lose the life of the bunny, that it can be transferred to this other puppeteer to swallow it. So yeah, all of that artistry, and the choreography of that and the craftsmanship that goes into it, not just making the puppets and making the sets, but also the way that they move and sort of the thought behind all of that. I find it fascinating.

A few years ago I got to go to this place called Puppet Heap, and they made the Muppets for the Muppet movie, and when I was there, they did a really cool thing, they brought me in and they asked me which Muppets were my favorites. I said, “You know, I love Kermit, and Janice, and Animal,” and then I kind of had my back turned, and they brought Kermit, Animal, and Janice out, and I got to play with each one of them. It’s really cool to have a character like Janice, who has a really long neck that will affect your movement in a way—Kermit, his neck is basically the puppeteer’s wrist—Janice, her neck is kind of the whole forearm. Even to me, I am by no means a puppeteer, but I have put my hand in a few puppets, and just see how each one is crafted and constructed, and how it informs what you do.

I was kind of bummed out when they did the ABC show, because it felt like, oh, that is going away from what they do really well, which are these little short vignettes. Everything that was in the original Muppets show was built for the internet. It’s these two-minute bits, whether it’s Animal and Harry Belafonte in a drum-off, or Rita Moreno having some weird dance thing in a saloon. When they did the ABC show, they threw all that stuff out the window, and went the exact opposite direction, and tried to create some long-form thing about Miss Piggy’s relationship with Kermit, and yeah, I don’t know, it felt like maybe it’s not your strong suit. Your strong suit was these videos you were doing before you even had a show, and before you even had those movies.

AVC: The assumption, when watching your special Brooklyn, is, “Nobody would make this who didn’t have a love of the Muppets.”

WC: Yeah, that was definitely part of it. There’s a great Sesame Street sketch about the subway, and it’s one of my favorite things. It’s on YouTube, it’s just a song about the New York City subway, and the whole thing is about how terrible the subway is, it’s just like the subway is awful. One of the lines in the song is something about “something just got in my eye,” and people are complaining about how it’s crowded, but it’s an upbeat, fun song, and when you see it, everything looks really dingy. It’s definitely the old image of dingy New York, and the subway looks ramshackle, but in the middle of all of this, in all of this complaining, it turns into a dance party, and all of these people, these characters are unified in their disdain for the subway, but that brings them together, they find this joy in it.

I think, to me, that was something that I thought about after we shot Brooklyn. I always wanted to add some sort of element, and I thought about animation, and about puppets, because I’m a fan of both forms of animation, both the sort of traditional and then puppets. But once we started putting it together, it felt like, oh, this is kind of my attempt to do a similar sort of comment on New York and how, if I got an opportunity to play with puppets, I want to try to honor as best I can that idea, like I had watching Henson stuff, where there was a humor to it, there was a darkness to it, there could be sadness, there could be silliness, that you could encompass all of those things.

Also, that comedy isn’t as simple as a hammer drops on someone’s foot and they jump and scream and fall down a flight of stairs. That is funny in itself, but there’s also, with comedy, you can take people on a journey. You can draw them in and make them feel an emotion, and create a tension that you then release with a joke, or that you can do all those things.

Jen Kirkman, “The Adorable Accident”

WC: It was funny, when I was putting this list together, I was trying to think of things throughout my time as a person who’s been fascinated with comedy or doing comedy, and to me this particular bit—I’ve known Jen for a very long time, and when I lived in L.A., I saw Jen do this bit before she had recorded it for the album. And so, in L.A. at the time, now Meltdown is considered the big show in Los Angeles that a lot of comedians want to do, but before that, there was a show called Comedy Death-Ray, and that was the show. If you were coming up, that was the show you wanted to do, because it was always sold out.

But there was also this very weird pressure in doing it because after the show, a lot of the audience members would go online and recap the show, and it was very weird. They’d recap the show, and they’d go through it and they’d say, “Oh, this person came in, and they told these jokes, and they were great,” or, “This person came in and they did the exact same set that they did six months ago,” and it was this very weird pressure that every time you had to do it, especially if you were coming up, there was this sense of, “Oh cool, I get to do Comedy Death-Ray,” and “Oh shit, I hope I don’t get slammed on this message board from people recapping this show.” [Laughs.] I think that was a paranoia that a lot of people felt.

And Jen was one of those people that I don’t think ever cared about that, and always seemed fearless whenever she approached doing that show, and was not afraid to talk about anything. This story is such a silly story, but it’s also a bit of great storytelling. Jen is such a great storyteller and it’s such a unique talent as a comedian to have—to be able to bring an audience in with you and convey something that draws the empathy out of them, that they feel like they know that dread when she’s in the bathroom, and that they aren’t just audience members, they are friends sitting across from her at a dinner as she’s conveying this story to them, and they’re just like, “Oh my god.”

I feel like you can kind of hear it in the bit, there’s almost this sense from the crowd that they want to respond with more than just the laugh. If you were watching her tell the story at a bar to a friend, the friend would say, “What did you do next?” That’s the same sort of response she’s able to elicit from audience members, and it really is such a great skill. To me, this story, hearing her tell it, exemplifies that well. And then has that little coda to it, the audio clip of her as a kid is just kind of like this sort of perfect weird coda to the whole thing.

AVC: It’s this beautiful “life cycle of a comedian” moment, like she’s always been like this.

WC: Yeah, she’s always been talking about shitting her pants. She can’t stop.

AVC: That’s kind of Jen Kirkman’s superpower. Intense bluntness is normally used as a distancing mechanism, whereas she wields her bluntness in a way that pulls people in and makes it relatable.

WC: Right, yeah. And it’s a real challenge to do that. I think anybody who gets on stage, it’s a challenge, however you draw anything out of an audience, it’s a challenge, and it’s always a skill that’s there. If you’re just doing one-liners, there’s a skill to the delivery of one-liners so that they hit properly.

Steven Wright can do Steven Wright very well. Not everyone can do Steven Wright’s jokes with the same results. I think back to this video from a telethon where it’s Chris Rock and Steven Wright, and they swap out their sets. And so Chris Rock does Steven Wright’s set, and Steven Wright does Chris Rock’s set, and there’s video of it online, I think. What’s interesting is you watch the two of them and it says something about writing, that these are funny jokes that each of them have delivered well for however many years for however many years they’ve been doing those jokes, and they clearly work, but what you also see is there is a difference when you’re doing someone else’s material versus doing your own. And being able to connect with an audience, and being able to draw something out of a crowd is a real skill.

That’s something that as long as I’ve known Jen, she’s always been able to do. And she really is to me one of the best storytelling comedians that I’ve gotten to see. We talk about Cosby—before we talked about Cosby currently [Laughs]—Cosby was always one of those people that people would say he’s the greatest storyteller, and that’s something I remember seeing Jen and thinking she is of that same mold. My hope would be in 20 years people go through her catalog in a similar way. Like, “Oh yeah, she was such a great storyteller,” although by saying “she was” I’m suggesting she’ll be dead in 20 years, which I’m sure if she read that she would then yell at me.

AVC: That will be our headline: “Wyatt Cenac thinks Jen Kirkman will be dead in 20 years.”

WC: “Wyatt Cenac predicts the death of your favorite comedian.”

Chris Rock, Bring The Pain

AVC: This is such a classic set at this point. I don’t know if there’s anyone who doesn’t at least respect this album, even if it’s not one of their favorites.

WC: It’s true. It’s weird, because when I was putting the list together, I had looked up when it had come out, and it came out like 20 years ago this week. In this weird way, I found myself thinking, “I kind of wish somebody would have one of those 90-second street-wide in-conversation type of things with Rock about Bring The Pain 20 years later.” Because, at least to me, it was such a big thing. I remember seeing it as somebody who wanted to do comedy and being blown away by it, but even now, it’s something that I still watch whenever I make an album or a special. It’s one of the specials that I go back and watch just to see from a performance standpoint, the way it feels like, “Oh, he attacks the stage,” and there was just this sharpness to everything.

They always talk about when athletes get ready for a game, they listen to music of some kind. For me, that special is one of those things that before I ever tape or do anything, I go back and watch that, and hope that I can attack the stage in my own way with the same sort of hunger and drive that it seems like was carrying him through that. And also just the writing of it, it’s just a well-put-together special. Where Jen is a great storyteller, Chris Rock—you look at a lot of those bits, and it feels like he goes about it almost like a scientist goes about an experiment. You can see the scientific method to a certain degree in his writing. He lays out a hypothesis, he has jokes, which are his experimentation phase, he goes through all the different steps of the scientific method, and eventually gets to a conclusion, which is his biggest laugh at the end of it all. Even in his experimentation phase, you see he’s big on finding a line or something that he can repeat, and repeat it to the point where sometimes he’ll get the audience to say it with him.

There’s a meticulous scientific way that I feel he goes about joke-writing where some of those bits are eight- and nine-minutes long. And there’s a sense of awe that I have looking at some of those things, because that’s eight minutes that you might take into a club, and anytime that I’ve had to work on a set for an album, I’ll go to clubs. You go to a club and get 10 or 15 minutes for your whole set, and if you’ve got a long bit like that, if you’ve got an eight- or nine-minute bit that you’re going to put in front a club audience, and people are listening in a club where there’s a drink minimum, and people can get rowdy, but you can get it out and keep them… that’s really impressive.

So when I watch that special, doing some of those bits, I just think about, “Wow, you were at The Cellar or The Improv or wherever you were, getting 10- and 15-minute spots to work on any of that stuff. “Niggas Vs. Black People,” to do that in a club and to polish that and polish that, and it probably didn’t start where it is now, so you really had to work on that and get that built right, and then you’ve got to go on the road and do the colleges, and you did it at venues on the road, and at clubs where you’re getting longer sets, but it started in a club in a 10-minute bit.

AVC: This is something that comes up a lot with classic comedy specials some years down the road, where there are these hot-button bits that you’d have trouble selling nowadays. Even his whole O.J. Simpson riff of understanding why he would kill Nicole—it’s hard to picture being able to do that today.

WC: Yeah, it is. But what’s kind of interesting about it is there is a part of it where you say, okay, it would be hard to get away with that, but also at the time it wasn’t a particularly easy thing to say. You can hear it in the audience, where the whole comment about hitting a woman and all of that, and he even says, “I would never hit a woman,” and you can hear and see the audience—“Where is he taking us with this?” And he still does that when he’s on stage now. Not that bit, obviously, but I think there is something to it that at that time, 20 years ago, domestic abuse was something that people were outraged about. And even 20 years ago, to even bring that up in a comedy set, I feel like, yeah, that was a huge challenge. You could really lose the room on it. This is something that could get you in trouble. But using it to make a larger point, that was sort of the skill that he has. It is, “Okay, they’re maybe going to hate you for awhile.”

I feel like I just saw some interview with him where he was talking about that, or maybe it was a clip from a documentary that’s coming out, where he’s talking about his experience with a joke. About how some people just like, laugh, laugh, laugh. And he was saying, “I kind of want laugh, boo, laugh again.” I don’t remember the exact quote, but it was something about taking people on a journey and challenging people’s beliefs on some level. I think that’s his skill, and he does it better than most.

What’s Alan Watching?, pilot

AVC: How have I never heard of this before? It’s insane. It’s a family sitcom where the kid watches TV and goes off and has these surreal fantasies and daydreams, featuring Eddie Murphy, among other people.

WC: Yeah, I feel like so few people know about What’s Alan Watching? I remember I saw it as a kid, and at the time I was obsessed with Eddie Murphy, and I would watch the Eddie Murphy Best Of SNL on loop. I had that VHS. That and the Bill Murray Best Of SNL were the two VHS tapes that I had, and I would always watch. I was obsessed with Eddie Murphy and somehow, I guess I must have seen a commercial for it, and then saw that Eddie Murphy was in it, and just parked myself in front of the TV until it came on.

It was at the time when CBS would air the pilots they didn’t buy over the summer, which I wish they did still. It’s such a cool thing. When you watch that show, it’s very clear they are never going to make a show like that. It was never going to get 22 episodes. But on its own, it’s a cool thing. You’re never going to make a show like that where you’ve got George Carlin and Eddie Murphy and these comedians, Alex Trebek, all doing cameos. But you look at something like Beavis And Butthead, and this feels like it’s similar DNA.

But it was just such a silly weird thing, and to see Eddie Murphy do that James Brown story, it always made me laugh as a kid, and just seeing him in a courtroom where it turns into a musical performance of “Please, Please.” That and “Ghandi On Ice” were two things that just made me laugh. Even “Ghandi On Ice” felt like such a Zucker brothers type of a thing, that was just so silly, to sort of start it off like it seems very serious, and it just goes to the silliest, most ridiculous place, and yeah, I think to my teenage brain, that was just like so silly and weird and different that Eddie Murphy was doing this silly, weird, very meta thing. The whole show was really meta.

For a long time, I would get in conversations with people, and be like, “Did you ever see the show What’s Alan Watching?,” and people would go, “No, what are you talking about?” I remembered Corin Nemec was in it, and I forgot Fran Drescher was in it… I don’t know how all those people are in the same family. [Laughs.] She’d clearly been adopted at like age 25, because she does not sound like the rest of the family at all.

AVC: It’s like something from Liquid Television from the mid-’90s, but then combined with these family sequences that are almost like a proto-Larry Sanders approach of no laugh track, single camera, weird digressions. It’s this Frankenstein monster of two styles that’s kind of jaw-dropping to watch.

WC: Yeah, and interesting in its own way, because at the time, I’m guessing there’s nothing else like it happening. I don’t know if other people saw it and were influenced by it or anything like that, but it feels like… people always talk about things that were maybe ahead of their time, and this definitely feels ahead of its time. It feels like somebody could probably try to do something like it today, and maybe they get six episodes. The fact that people took a chance on it then, with nothing else to compare it to… if you tried it today, you could pitch it like a live action Beavis And Butthead, or Liquid Television, there’s so many things that you could kind of link it to.

Even just for Eddie Murphy to be an [executive producer] of it, to back it, speaks to him seeing something about this meta, weird kind of comedy that he’s into, and that at that time, he was like, “Yeah, let’s do that, that seems cool and weird and fun, we won’t necessarily think about the consequences of ‘If we get an episode two, how are we going to convince Dan Aykroyd to dress up and do this?’” There’s a sort of Funny Or Die element to it too, where you have all these cameos. Even just Corin Nemec filming things in his school, even that’s weird to look at now and think about, “Back then, there probably weren’t a lot of kids walking around with a giant camcorder on their shoulder, filming people as they walk through school.” But now, that’s common. There are videos littering YouTube, just shooting anything and everything they see in school and in life. So yeah, it seems very ahead of its time—you could look at it and be like, “Oh wow, they were predicting the future!”

Russ Parr—Bobby Jimmy & The Critters, “Hair Or Weave”

WC: As we continue to go back in time, this was something I saw as a kid, and I remember at the time, maybe a few years before this, they were playing Weird Al videos on MTV, and “Eat It” was the song of the summer for kids my age. It was so huge. And then when this song came out, and Russ Parr was a guy, I would hear him on Dallas radio a lot, where I grew up, he had a few of these types of songs.

But I just remember seeing a video and there was this part of seeing it that, to me, was an accessibility thing. So many of the comedians that I would see on television, a lot of them were white dudes. Outside of Eddie Murphy and Bill Cosby, until you had the ComicView and Def Comedy Jam, you didn’t really see a lot of black comedians, but when you did, a lot of comedians on Def Jam had a similar style, and a lot of the comedians on ComicView had a similar style. As a kid, it felt like, “Okay, if I’m black and I want to do comedy, to succeed, you have to be like this, you have to try to think of comedy in these terms, because this, just looking at it from what the market has determined, this is what succeeds.” So to see this, and at the time, too, I think Arsenio Hall started doing stuff with his alter-ego Chunky A, and these were just weird things, and there was something about where I felt like, “Oh, you can also do weird stuff.”

Because even though I find Weird Al funny, I didn’t fully go down those roads. It was, “I find Weird Al funny, but I’m not going to put on a Hawaiian shirt, I’m not going to be that kid.” But then it was Russ Parr, and Russ Parr was on Yo! MTV Raps, so there was this element of, “Okay, I can talk about Russ Parr to kids, to my friends, and they think Russ Parr is cool, too.” Bobby Jimmy, everything about it is silly and goofy, and that’s fine.

Even In Living Color, that also just opened up this world for a diversity of what comedians of color could do, and could present and succeed in the world. So for me, seeing Bobby Jimmy, or seeing Arsenio, or seeing In Living Color, comedians that were doing different things than what it seemed we were saying black comedy should be, that meant a lot to me as a kid growing up. That I can do different stuff and I can also still appreciate comedians of all colors and different genders and stuff, but that—beyond appreciating them—there are comedians who are doing different things who look like me and are succeeding doing those different things.

AVC: It’s very much in the tradition of a Weird Al or Dr. Demento, where it’s so goofy and silly and jokes upon jokes, but also, it’s not shying away from having a clear connection to black culture.

WC: That’s what’s so great about it. We look at the world from a default point of view, and anything outside of the default, especially once you get TV network money involved, there’s this, “Well, we have to make it acceptable to everybody.” And what’s interesting about this, and what’s great about a show like Yo! MTV Raps, was there was no attempt at making it accessible, it was just like, “No, this is what exists, and you either like it or you don’t.” If you like it and you’re interested, if you don’t know what a weave is, now everybody knows what a weave is.

But I remember being a kid, and when that song was popular, being around white kids who didn’t necessarily know what a weave was. It then opened up a conversation, or they had to go find out. They then learned something, and they saw an extra dimension to people that maybe they weren’t aware of. That’s what’s also kind of nice, there isn’t a four-minute preamble of, “Let me explain the history of black hair to anyone who doesn’t understand this.” No, this is a thing, and if you get it, great, and also, to anyone who’s not of that culture, there’s a certain pride one takes in, “Oh, I know what these things are. I know what this is.” And to those who don’t, there’s an aspect of, “Ooh, I need to learn, and I should try and find out.” If that’s a way that gets people to learn or try to be empathetic to other cultures and other types of people, then maybe there’s a hidden benefit to it.

AVC: That argument about making shows as mainstream as possible just doesn’t add up, because when have suburban white kids ever not wanted to explore black culture? That’s always been the case.

WC: No, that’s true. That’s what’s kind of interesting even now when you look at how things get made and people get so caught up in demographics and who can be a lead of a show, and people get so weirdly protective. “Well, we don’t know if somebody would watch a TV show with an Indian lead.” But it’s like, yeah people will, because there are suburban white kids who are curious about Indians in the same way that they’re curious about black people, in the same way they’re curious about cultures that they’re not around.

But then, an even greater thing to me is that there are kids who are watching those shows that now think this is a road that is available to them, that they are creative individuals who can now go down this path. There’s a kid right now who is watching Master Of None and seeing somebody like Aziz or Mindy Kaling and thinking, “Oh, okay, it’s okay for me to like comedy, and it’s okay for me to delve into the other weird channels of comedy that exist and maybe try this myself.” Looking at stuff like In Living Color and seeing somebody like Eddie Murphy but also seeing somebody like Russ Parr making those weird music videos, to me, it felt like, “Oh okay, I can do this, and there is a space for me, and if I keep at it and really invest myself, then I can do this.” I look at some of that stuff and I think with a video like that and with a lot of the stuff I would watch as a kid, the underlying message it was giving me was of “Yeah, you have access to comedy as well.”

AVC: Don’t you kind of love the idea that there’s some young black kid in the middle of Wyoming somewhere who’s watching your comedy special or the old Chappelle Show bit with the puppets and thinking, “Wait, other guys are obsessed with puppets and can do stuff with them? I can do that?”

WC: Yeah. It’s sort of a sad thing about the whole story with [Elmo puppeteer] Kevin Clash, one of the unfortunate things—that was sort of separate from all the other unfortunate things— was there was a documentary that had been made about him. He was a kid in the D.C.-Maryland area, and he was interested in making puppets, and he was making puppets down there on his own, and then wound up getting connected with a puppet maker who had his own show, and over the course of the documentary, they find another kid like Clash, they found another black kid who was 12 or 13 years old who had been making puppets and then they put that kid in front of Kevin Clash. It was kind of, “Oh, it’s great that this kid gets to see this,” but yeah, as a person who has for years tried to sell puppet shows, I wish there were more kids of color that were like, “We want to make puppets too!” So then somebody would say, “Oh, there’s a market for this, all right, yeah, okay dum-dum, you can make your stupid puppet show. We’ll give you a chance to make your puppet version of What’s Alan Watching?”

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)