Wyatt Cenac’s latest album finds the funny in world-weariness

In the audiobook version of That Is All, the final book in John Hodgman’s gloriously detailed trilogy of fake knowledge and real wisdom, there’s a story within a story about a science-fiction writer telling of his friendship with the mysterious (and also fictional) Anne D. Egan. Performed by Wyatt Cenac, the reminiscence plays out in wistful yearning, Cenac’s measured cadence encompassing the odd tale’s mix of meticulously imagined mythology and personal loss with an immediacy belied by Cenac’s unobtrusive voice. In a book full to bursting with different voices and styles of storytelling, Cenac’s contribution strikes a deeply human tone of plaintive regret.

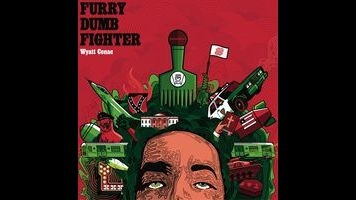

Such a quality might seem incongruous with a career as a stand-up comedian, but it’s Cenac’s seeming detachment that makes the material on his new album, Furry Dumb Fighter, resonate as much as anything. With his heavy-lidded eyes and hint of a drawl (the Brooklynite Cenac grew up in Texas) that innate weariness of tone could suck the life out of the jokes, but instead it creates a rolling storytelling vibe that’s authoritative and funny. Noting people’s perception of him as a shaggy stoner throughout, Cenac explains, “People think I’m high all the time, ’cause I talk kinda slow. And look like a high school jazz teacher,” and relates an anecdote ending with him being referred to as “sleepy Cornell West.” He does cop to receiving not-unwelcome gifts of weed after shows, culminating with a mixed-blessing present of an ungodly amount of pot at a gig across the country. (“That is a very generous burden for someone who does not live in San Francisco.”) But, as his ultimately ill-fated gig on The Daily Show revealed, Cenac’s incisive takes on issues like race, sexism, religion, and the American psyche come couched in a diffidence that’s all the more authoritative for how little effort he appears to put into proving his point.

Political comedians, which Cenac definitely is, must develop a persona to sell their material, and Cenac succeeds in making his stuff emerge like something so sensible that all he can do is ruefully chuckle at it. That delivery is part of it, certainly—when Cenac addresses the Confederate flag issue, his discursive style sees him take detours to mock the self-satisfied people who view the growing ban on the flag as a victory against racism itself, chiding, “We can all sleep soundly knowing that the Confederate flag will never fly over a Seattle yoga studio.” A second detour sees him admitting that racist states do always come up with great flags, saying, “There is something about terrorist occupations that brings out the best in graphic designers.” In picking apart the issue from unexpected angles, Cenac’s voice in decrying the racism within it comes through with that much more power—even if, as he admits later on the album, a comedian simply stating truths rarely has much effect. (“If it feels like I’m pandering, I am…”)

Again, such a defeatist attitude could enervate Cenac’s act, but the comic has a light touch rooted in a still-hopeful plea for simple fairness, basically. Relating New Yorkers’ ability to put aside their differences in ignoring “a folk singer with blond dreadlocks” begging on the subway, Cenac jokes that it fills him with hope for humanity when “a guy in a Jets jersey and a lady with an NPR tote bag” can “agree to ignore a person.” He builds the bit skillfully, parceling out the punchlines with expert timing that his Madison, Wisconsin, audience greets with appreciative laughter. (Cenac does some amiable crowd work throughout the album.) When he ends the bit with, “We can do anything after that,” its catharsis comes more from the recognition of common humanity than from any specific target.

Playing up his nerdy credentials throughout (the Avengers, Captain America, Game Of Thrones, and Star Wars references abound) Cenac’s self-effacement, too, leavens some of the material’s potentially preachier qualities. Inserting himself into a Black Lives Matter protest after police killed Eric Garner, Cenac portrays himself as both deeply moved by the experience, and as someone whose inability to not look for inconsistencies is always going to set him apart. Musing that the New York City police got $18 million in overtime for the march, Cenac suggests, “That’s why they were so cool with it,” and posits that all that money might be better served addressing the root problem. (Noting that the $2 million spent policing Occupy Wall Street is enough to start a hedge fund, he suggests, “We could have just donated $2 million to Occupy Wall Street… and then they could have camped out directly on the Wall Street trading room floor and fucked shit up from in there.”)

Cenac’s act here has a writerly feel (it’s tighter than his last one, and his segues are especially smooth), with this and other pieces flowing according to well-crafted blueprints that, in his delivery, roll out with a deceptive spontaneity. Sometimes, as in the Garner section, the punchline (a connection between basketball star Carmelo Anthony and the police proving that New York has “a problem with overpaying dudes who shoot too much”) can seem too neat, but there’s a fanciful playfulness along the way that makes the journey enjoyable nonetheless. Citing the outpouring of crowdfunded donations for the likes of Trayvon Martin’s killer George Zimmerman (who received over $100 thousand after shooting the unarmed young black man), Cenac expresses genuine outrage (“What’s the fucking going rate on killing a kid?”) while, in the next breath, musing that at least it probably does prove that America’s economy is doing pretty well. Similarly, when bits about topics like spousal rape laws, slavery, and police violence digress into asides about the sexual politics of The Honeymooners, time travel, and The Lego Movie, respectively, Cenac keeps them on point, often snapping the bits off with a dark gag that elicits some gasps from the crowd. His Thomas Jefferson material covers old ground—the founding father had sex with people who were literally his property—but still, in Cenac’s delivery, it lands with a sting. (“Let’s not forget old Mount Rapemore.”)

Not everything works. While Cenac does admirable work in couching it in his ongoing examination of cultural double standards with regard to celebrity and wealth, a 12-minute piece about Kim Kardashian is a lot. But Furry Dumb Fighter’s expansive 72-minute running time has room for a lot of great material, with Cenac deftly lacing shorter laugh lines through the weightier stuff. For every extended metaphor of America as “England’s trust fund kid, who rejected everything to open our own artisanal freedom shop,” there are observational bits about how that cultural self-aggrandizement, for example, imported the world’s most popular sport, only to give fútbol “a slave name.” His personal material is uniformly solid, whether reacting to past quotes in support of Bill Cosby with a series of panicked shrieks and the cry, “Sweaters, hoodies—I am fucked for the winter,” or relating the concluding story of being arrested for reporting his own car stolen (“Well, I do fit the description of ‘somebody’”). Cenac has a singular take on the world around him, one that blends world-weary intelligence with a playfulness that suggests there’s still hope—even when that world is wearying indeed.