The cognitive dissonance sets in early, maybe at the first sight of a car. We’re in Paris, that much is clear. Armed stormtroopers patrol the streets, setting up checkpoints, issuing a familiar demand: “Your papers, please.” A German man, Georg (Franz Rogowski), haunted and desperate, is fleeing a wave of fascism that’s engulfed Europe. There is talk of camps and cleansing, words that have burned themselves into the historical record, onto the collective memory of World War II. But something’s off. The cars don’t look very 1940. Neither, come to think of it, do the clothes. These details tug at the verisimilitude, undermining any sense of certainty about the timeframe. And then someone speaks of a movie about zombies in a shopping mall and it becomes impossible to ignore the anachronism any longer. When, you have to wonder, is this film set?

The answer, as it turns out, is an indeterminate “sometime”: a then and an earlier then and maybe, by extension, a right now. That’s the tricky genius of Transit, a period piece whose period remains pointedly tough to pin down. The film is based on a novel by Anna Seghers, published in 1942, that very explicitly situated itself in then-current events, against the backdrop of the Nazi occupation and under the shadow of Hitler’s war machine. But Christian Petzold, the German writer and director, has taken some rather dramatic liberties with the source material, just as he did in his earlier Jerichow, which twisted the context and altered the ending of the oft-adapted noir classic The Postman Always Rings Twice. Here, he’s collapsed last century into this one to get at how the horrors of the war have played out again and again on the international stage, history repeating itself ad nauseam. If there is a certain cowardice to telling stories about the past to obliquely comment on the present, Transit sidesteps it by obliterating the distinction between them.

One could call it a companion piece, of sorts, to Petzold’s last movie, his masterpiece Phoenix, which was very unambiguously set during the aftermath of WWII. Undefined setting aside, this too is a story of survival and guilt and identity, an elegantly compact thriller with shades of Hitchcock and Carol Reed. Doubles and doppelgängers factor again into Petzold’s new-old genre equation. His hero, Georg, manages to make it to Marseilles, only to find himself ensnared in a moral and bureaucratic quagmire. He moves into a hotel occupied by fellow illegals—an unsafe haven constantly raided by the authorities—carrying the literal and figurative baggage of two less lucky souls, both deceased writers. One of them, who dies of gangrene during the voyage, has left behind a family: Melissa (Maryam Zaree), an African immigrant, and her young son, Driss (Lilien Batman), who Georg befriends. The other has committed suicide in Paris. Georg, carrying his belongings, assumes his identity as a possible means of escape. He also keeps running into a young woman, Marie (Paula Beer), who confuses him for someone she’s lost.

Petzold navigates this thicket of complications with what’s become his trademark efficiency and restraint. Transit, at a lean and precise 101 minutes, is only ever intentionally baffling—you can get lost in its mysterious muddling of era, but the storytelling itself is economically direct, with no extraneous scenes or even shots. He’s taken great care to make his twilight zone Europe feel both like a real place and unplaceable: Neither the costume nor production design betrays a specific decade, though the latter is partially a byproduct of how much time the film spends in offices and cafés and hotel hallways—mundane spaces that haven’t, all things considered, changed that much in half a century. One of the filmmaker’s more giddily destabilizing choices is the voice-over: unreliable narration from a largely unseen character, which offers third-person insight into Georg’s thought processes while also describing events differently than how they unfold before our eyes. Does this mismatch say something about the small and large ways we distort history, and are hence doomed to relive it again and again?

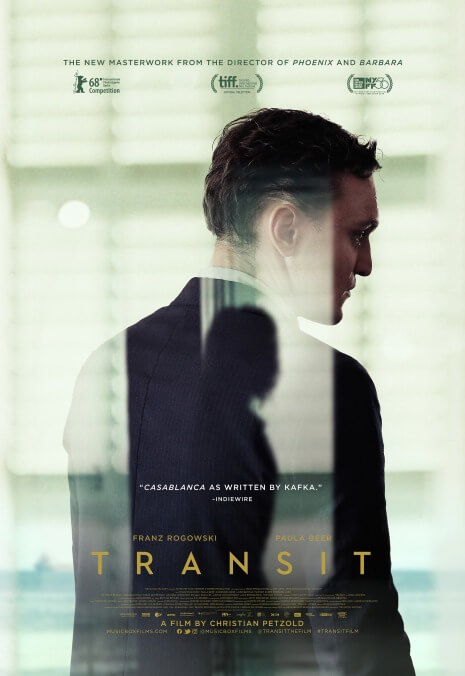

In Phoenix, Petzold riffed on Vertigo, reconfiguring that classic’s disturbing roleplaying games into a meditation on national identity. There’s a touch of a different touchstone, of Casablanca, in the love triangle of sorts that links Georg to the almost ephemeral Marie and her paramour of possible convenience—a doctor, Richard (Godehard Giese), also looking for a way out. Yet the relationships hinge less on desire than a shared feeling of helplessness and perhaps unresolvable responsibility: As survivors, they have all committed deceptions and left people behind, which gives their romances—overlapping, like the time periods—the weight of tragedy. Much of that weight falls on Petzold’s remarkable lead. Rogowski, whose cleft palate and lanky frame mark him as a phantom double for Joaquin Phoenix, somehow makes Georg both present and absent at all moments, locating the emotional reality of his dislocation. He is a ghost in the most existential sense, someone caught between worlds. Which, of course, is what Transit is really communicating: the heavy truth that to be unmoored from country is to be unmoored from self.

In other words, this is a film about the maddening uncertainty and loneliness and, yes, cognitive dissonance of the refugee experience. Unable to stay or go, to save himself or anyone else, Georg gets caught in a Kafkaesque limbo state; for him, Marseilles is one big waiting room. (As his dead-writer counterpart eloquently, explicitly explains, purgatory may be more hellish than hell itself.) Timely but really timeless, which is maybe the whole point of its nebulous temporality, Transit doesn’t just freeze its characters in place. They’re stuck in time, too, on a continuum that connects today’s exiled lost souls to yesterday’s. Because when it comes to people without country fleeing for their lives across the globe, there is no old or new, no then or now, no past or future, just an awful present tense. Transit, meanwhile, looks from this present tense like an early contender for the best movie of 2019. Or wait, is it 1939?