Nothing is ever as it seems in film noir, a genre built on hidden motives and delayed revelations. Serenity, a preposterous tropical-island thriller from writer-director Steven Knight, takes that principle to an absurd new extreme. To even describe the film as noir is to make oneself an accomplice to its deception. This is the kind of movie, easily spoiled at a slip of the tongue, whose entire raison d’être is its twisty architecture—and the underlying conceit is, admittedly, pretty fun, or will be for those who take pleasure, guilty or otherwise, in stories that raise big, obvious questions about the nature of reality. But though Serenity is blessed with a goofily enjoyable high concept, it doesn’t exploit it very effectively. You can make the viewers detectives themselves, allowing us to slowly unravel a mystery, or you can give up the charade early and just run with the premise you’ve opted not to conceal very carefully. There’s little sense in doing neither.

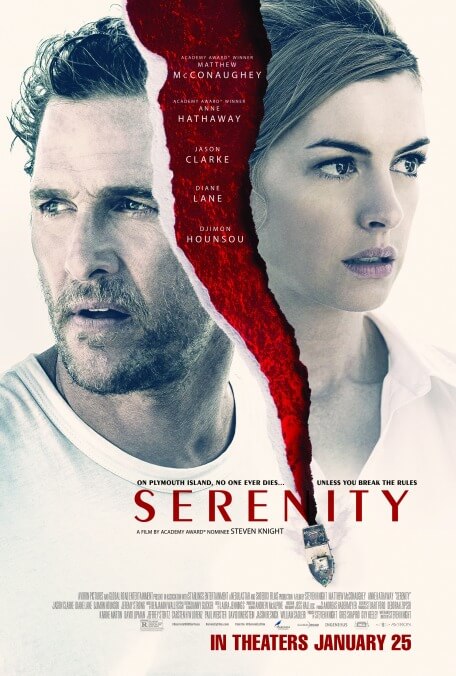

The setting is a secluded island called Plymouth, a cozy enclave where everyone knows everyone, in part because there’s only one bar and nothing to do but fish, drink, and screw. Where precisely is this seaport situated? It’s unspecified, pointedly. Summoning a little unshaven Bogartian grit, Matthew McConaughey is Baker Dill, a fishing-boat captain who passes his days on the ocean with tourists and his exasperated first mate (Djimon Hounsou) and his frequently sleepless nights knocking back bottles of rum or knocking boots with a moneyed local (Diane Lane). What really keeps Baker going is a crusade worthy of Ernest Hemingway: his single-minded obsession with catching a fabled oversized tuna named Justice that haunts the island’s collective imagination. Perhaps it’s just a way to keep his mind off the time he spent fighting in Iraq, or other aspects of his troubled, mysterious past.

That past doesn’t stay mysterious for long. In fact, it comes waltzing right back into Baker’s life in the form of Karen Zariakas (Anne Hathaway), his ex-wife and high-school sweetheart. Karen left Baker, back when he went by a different name, for the wealthy Frank (Jason Clarke), who’s revealed himself over time to be a violent, sadistic brute. Now she’s returned, decades later, with a proposition: $10 million in cash to take her second husband out on the water and leave him there. Her real bargaining chip isn’t the money but Patrick (Rafael Sayegh), the son she had with Baker a lifetime ago, who he still sees in his dreams and talks to in his loneliest moments. Patrick’s now a preteen genius who escapes the tantrums of his stepfather by holing up in his room and disappearing into his own time-killing obsession, computer games.

This is the point where anyone with even a passing familiarity with stories about unlucky guys talked into murder plots by desperate dames will start asking questions. Is Karen telling the whole truth or is she looking for a patsy? (Hathaway, keeping her cards close to the chest, offers a mix of cunning and vulnerability any good femme fatale should possess.) But though Serenity has the superficial shape (and warm weather) of a Body Heat, it’s blatantly up to something else; right from the jump, the film practically begs for a deeper level of suspicion, like a killer haphazardly spilling evidence on his way out of a crime scene. What’s up with the milquetoast, slightly off-kilter salesman (Jeremy Strong) racing around the periphery of the story? And how come everyone Baker encounters knows more than they should about what’s going on in his life? Even the film’s style, characterized by conspicuous crosscutting and stuttering camera pans, is loose-lipped, threatening to let cats out of bags.

As a screenwriter, Knight has dabbled in noir (see: his Oscar-nominated script for Dirty Pretty Things), as well as tricky puzzles of identity, via the undercover spy games of Eastern Promises and Allied. But Serenity is maybe closest in spirit to his overpraised Locke; like that one-man, one-car show, it often plays like a glorified exercise. Knight, to his credit, does find occasional fun toying with the conventions of his adopted genre: the shadows cast by rotating ceiling fans, the slits of narrow light streaming in through nearly closed blinds, the hard-boiled patter of his dialogue. (“Just waiting on some things back home to lose their significance,” Baker tells his ex—and, if nothing else, the Lincoln spokesman playing him knows how to make a meal out of shopworn lines.) That the whole thing is heavy with cliché actually makes a kind of sense, given what’s really going on. That’s probably saying too much.

Plenty of writers get the urge, at some point, to deconstruct the tenets of storytelling. Charitably, Serenity could be called an attempt to poke around under the hood of drama itself, to allegorically tinker with its moving parts. In practice, it’s a nutty idea in search of a movie, and Knight mishandles it besides, showing his hand too early and stepping on the sense of discovery by having a side character literally blurt out his big bombshell. Even with McConaughey sweating magnificently through the reveals, the film never taps into the true existential terror of its premise, the way… well, to even draw a pertinent comparison would give up Knight’s game. In the end, Serenity just deepens your appreciation for other movies—the “real” noirs it’s deceptively evoking, and the puzzle box mind-blowers that understand, at very least, that a good gimmick is a terrible thing to waste.

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)