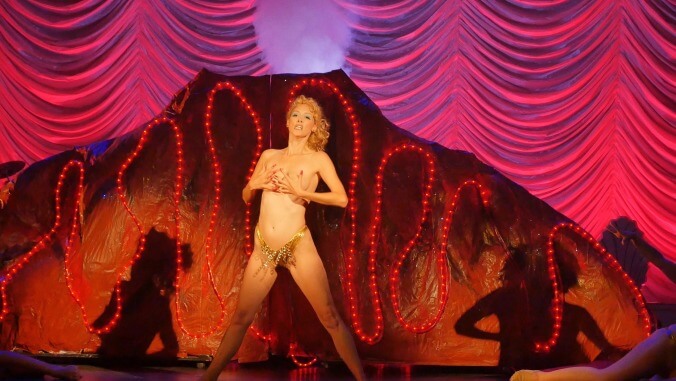

A much-maligned critical and commercial flop at the time of its release that became a surprise hit on home video (it ranks as one of MGM’s top 20 bestsellers), Showgirls has subsequently found new life as a beloved cult movie of outsized proportions, an exemplar of campy entertainment on par with Mommie Dearest or Valley Of The Dolls. Jeffrey McHale’s documentary examines the movie’s unlikely second coming, the better to understand why it has found such a devoted and enduring following. It’s essentially a visual essay, putting all the good and bad of its subject up there on the screen to be picked apart and interpreted as its proponents and detractors see fit.

Smartly relegating all the talking heads to the role of unseen commentators (save for the archival footage of actors and creators involved with the film, reflecting on it at the time and in the years thereafter), You Don’t Nomi incorporates clips from Verhoeven’s other films, intercutting them with scenes from Showgirls to place the latter in the larger context of the director’s career. It looks at the way the film’s reception affected its own creative team (star Elizabeth Berkley was all but blacklisted in Hollywood) while also tracking the joy, inspiration, and even catharsis fans have found in its tale of an intense dancer coming to Vegas with dreams of stardom, climbing the ladder of success in a loose All About Eve narrative (with Gina Gershon as the Bette Davis to Berkley’s Anne Baxter), and finding only corruption and darkness.

If the hope is that viewers will leave this film with a deeper appreciation for the genuine oddness of Verhoeven’s splashy and expensive mid-’90s misfire, mission easily accomplished. Even those familiar with the movie’s origins or its current status as Rocky Horror-style “participation encouraged” cinema will likely find new assessments to mull over. The most entertaining contributor to the constant stream of voice-over commentary is longtime writer and performer David Schmader, whose own role in the film’s journey serves as a kind of pivot point: After a number of years performing live comedic commentary during public screenings of Showgirls, MGM reached out to Schmader to have his withering and hilarious routine included on a DVD release, marking the film’s public transformation from embarrassment to so-bad-it’s-good milestone. Not everyone shares Schmader’s amused appreciation: Nayman firmly believes that even the movie’s bad elements sit in tandem with its artistic brilliance, while revisionist attempts by Verhoeven, writer Joe Eszterhas, and others to retroactively claim they were making a secret comedy all along are fairly easily discredited by statements made at the time.

But You Don’t Nomi’s look at the responses to Showgirls gets serious—and surprisingly moving at times. Critic Haley Mlotek makes a compelling case that the film is inherently misogynistic (noting both Eszterhas’ and Verhoeven’s off-camera behavior), but her words are immediately followed by an affecting counterpoint from April Kidwell, the actor who portrayed the lead role of Nomi in a campy off-Broadway adaptation of the film (and who also—irony alert—had previously played Jessie Spano, Berkley’s breakout role, in a similarly farcical stage parody of Saved By The Bell). Describing her own sexual assault, Kidwell opens up about how Showgirls helped her confront and process her trauma, the film’s oft-castigated subplot of rape and revenge therapeutic rather than appalling to her. It doesn’t excuse the movie’s sexism or racism (both of which are pretty hard to deny), but it does cast light on how Showgirls can be empowering and aggravating at once.

According to You Don’t Nomi, that bifurcated reception seems to define the film’s legacy. It operates as a gross and laughable tale of less-than-one-dimensional women but also works as a Starship Troopers-like subversion, where you “almost feel as though a prank got pulled on the studio,” as one discussant puts it. The poet Jeff Conway describes it as “impossibly bad, and thrilling at the same time.” The drag performer Peaches Christ, who’s restaged the film over and over, sees the humor in it but has also sought to emphasize what’s scary about it. And Schmader, who continually delivers the best lines of the documentary, loves the film beyond measure, even as he describes it as seemingly “written by a 13-year-old imagining what adults do at night.” It may not be as bizarrely entertaining as the film it obsesses over, but You Don’t Nomi is a captivating document of how a piece of art—especially one this deeply, powerfully weird—can take on a life wholly beyond its original intentions.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.