Dusty post-apocalyptic sci-fi, stripped-down Western, soberly tragic melodrama: Writer-director Jake Paltrow blends multiple genres and stylistic tics in Young Ones. (Even the end credits, during which the actors strike fourth-wall-breaking portraiture poses, resemble the cast roll call in a ’30s Hollywood programmer.) Would that there were more beneath the surface of this strange brew, but it’s certainly compelling while it lasts.

Divided into three chapters (each section is announced on-screen by a big, bold supertitle), the film is set at some unspecified time in the future when water is in short supply and Earth has become a mostly barren wasteland. The Holms—father Ernest (Michael Shannon), and children Jerome (Kodi Smit-McPhee) and Mary (Elle Fanning)—are a family of farmers who live on a patch of arid acreage that barely supplies them with the basic necessities. Former alcoholic Ernest sells bottles of liquor that he brews to make ends meet. Gawky Jerome is in thrall to his dad, but the rebellious Mary, who blames Ernest for the accident that crippled their mother, is not. Enter the duplicitous Flem Lever (Nicholas Hoult), son of a local merchant, who insinuates himself into the Holms’ life, first as a nuisance (he dates Mary against Ernest’s wishes) and eventually as a threat.

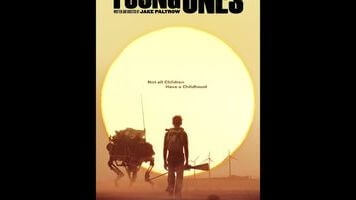

Paltrow and his cinematographer Giles Nuttgens do a superb job realizing this grubby world of tomorrow, shooting in expansive widescreen that occasionally packs the punch of prime George Miller. There are many languorous dissolves (goosing up otherwise mundane dialogue exchanges) and graphic-match jump cuts (a midnight moon suddenly becomes the noonday sun), though it’s the Holms’ robotic assistant—which walks around on four spindly legs, backlit by magic-hour skies—that’s the subject of the most evocative imagery.

This, however, points to the film’s main problem: The aesthetic trappings are much more interesting than the people. Shannon is unsurprisingly the best of the central quartet, a ruggedly tender presence (he and Smit-McPhee have a genuinely lived-in rapport) who still seems as if he could let loose at any moment with a display of volcanic rage. That he keeps himself in check for the most part only heightens the tension of his every moment on-screen, yet despite his top billing (and true to the film’s title), it’s Smit-McPhee and Hoult who end up claiming the main focus.

The former does reasonably well by Jerome’s transition from awkward innocent to avenging angel; the scene in which he discovers the full scope of Flem’s deception is effectively captured with a series of Falconetti-like close-ups, shock giving way to copious tears. But both he and pretty-boy Hoult ultimately make for an ill fit with the story’s stoically retrograde machismo, which also leaves Fanning in its wake. (She’s little more than XX window-dressing, an object to be fought over, manipulated, and impregnated as the narrative dictates.) Lived-in as this world appears, none beside Shannon seem like they should be living in it.