Yuichi Yokoyama’s Iceland highlights how loud comics can be

Comic books are a silent medium, but that doesn’t mean they can’t be loud. Yuichi Yokoyama’s comics are a prime example of this, and he creates gekiga (his preferred term over “manga”) that are fixated on the relationship between sound, images, and time. Iceland (Retrofit/Big Planet) is a new translation of Yokoyama’s 2015 sequel to World Map Room, but readers don’t need any prior knowledge to jump right in: These are not books driven by plot or character.

Iceland’s vague story provides some semblance of a journey—the characters end up in a different place than where they started—but it mostly serves as connective tissue between abstract sequences that will elicit different reactions from different readers. Yokoyama began his career in the world of fine art, and he brings that sensibility to his comic-book storytelling, prioritizing intense sensory stimulation over a clear-cut narrative.

Iceland opens with a sequence revealing the frozen setting: It’s serene and quiet, with orderly rows of icicles hanging across the snow-covered landscape, light shining off them in sharp Xs that make the environment glisten. The volume is low for the introduction of the two main characters, but once they start on their path to find their third companion, that volume turns way up. The introduction of a fisherman brings a rush of noise as he turns on the mechanism that pulls a shark out of the frigid water, the sound effects growing in size with each step of the process.

Upon entering a bar, the characters are bombarded with sound from the movie being played, and sound effects are paired with aggressive wartime images like rockets flying through the air and soldiers shooting their weapons. English translations of the sound effects are printed on the page, and their uniformity draws extra attention to the power of the original Japanese sound effects, which take up much more space in each panel to reinforce their volume. This book would be severely diminished if those original effects were to disappear in translation, and Yokoyama’s work shows the benefits of making sound effects a key part of the original panel compositions, rather than something added afterward by a letterer.

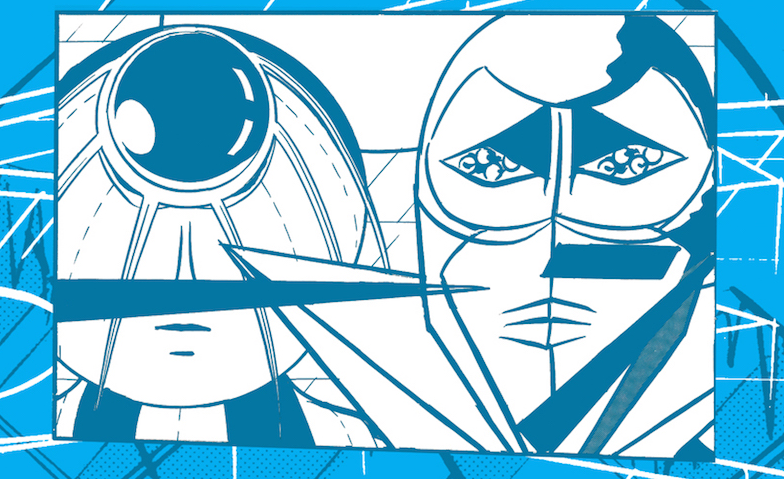

“They were nobodies,” a character says at the end of Iceland when describing the central duo, and it’s an apt description, given their lack of personality. These characters may not do much, but they function as bold visual elements with their strange, geometric designs, which is more important to Yokoyama’s general intent than making them distinct individuals on an emotional level. Readers that need that kind of character development to engage with a story won’t get much out of Iceland, but it offers a lot for people who appreciate visual abstraction and seeing how a person’s unique perspective shapes a story in unconventional ways.