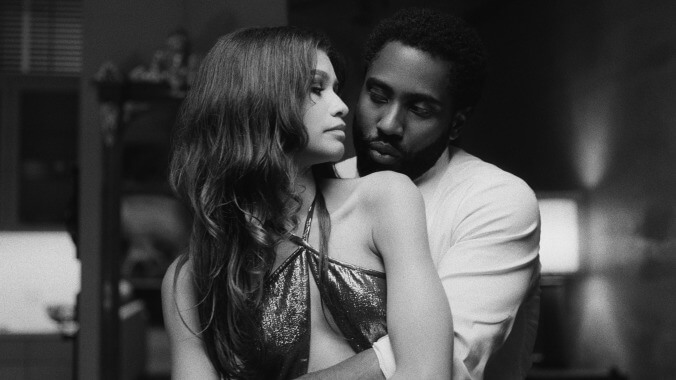

Zendaya and John David Washington spar—and rage against reviews like this—in the dull Malcolm & Marie

Note: The writer of this review watched Malcolm & Marie on a digital screener from home. Before making the decision to see it—or any other film—in a movie theater, please consider the health risks involved. Here’s an interview on the matter with scientific experts.

“I promise you, nothing productive is going to be said tonight,” Marie (Zendaya) tells her partner, Malcolm (John David Washington), near the beginning of Sam Levinson’s strident romantic drama Malcolm & Marie. It’s one of the few lines of dialogue in the movie that rings true, though probably not for the intended reasons. Then again, who are film critics to discern a filmmaker’s intentions? It’s impossible, contends Malcolm, an arrogant director who spends much of the movie bearing his name ranting about the incompetence of his critics—how they only compare him to other Black directors instead of William Wyler, how their desperate attempts to be woke in print blinds them to the apolitical beauty of craft, and so forth. Just accept the beautiful mystery of art, he all but instructs, and keep your assumptions about the artist to yourself.

Levinson, acclaimed creator of HBO’s Euphoria, devotes long stretches of Malcolm & Marie to the airing of industry-related grievances, all of which will sound familiar to anyone who obsessively keeps pace with media discourse on Twitter. Strip away all the inside-baseball stuff and what’s left is a standard two-hander notable mostly for having been conceived and filmed during an ongoing pandemic. Malcolm, like Levinson, has just finished a new film, an addiction drama that ostensibly spotlights the inequities in the health care system. At the premiere, he fails to thank Marie—an egregious oversight, considering the direct inspiration he took from her real-life struggles to get clean. Returning to their beautiful L.A. home, the two engage in a protracted screaming match about the state of their union, covering everything from his narcissism to her justifiable feelings of being constantly unappreciated and overlooked. In between intense confessions and cruel jabs, they also digress into discussions of privilege and the relative value of authenticity in art and the futility of holding radical politics while working in commercial film.

One irony of Malcolm & Marie is that its vindictive bellyaching about judging a film on its own terms is much more interesting than the actual relationship at the center of the film. The performances remain trapped in a self-conscious mode, merely mimicking the cadence and tempo of a romance-fracturing fight. Zendaya pulls off Marie’s cool, resigned frustration, occasionally conveyed through biting sarcasm, but she’s less convincing at full volume because there’s little variety in the tone of her speech. Meanwhile, Washington is saddled with the worse material, including an eight-minute tirade against the presumptions of a glowing review. But the material can’t entirely be blamed for a performance that modulates between voice-shaking whisper and a grating scream. You rarely perceive the characters themselves, only the actors playing them, which might be a blessing in disguise, given how profoundly dull these beautiful, comfortable people are, their vulnerability far from inherently interesting.

When John Cassavetes stages a fight scene between intimates, it feels reckless and discomfiting, like anything destructive could happen at the least expected moment. The fight in Malcolm & Marie, while clearly indebted to Cassavetes (though Levinson might reject the comparison), feels calculated at every turn, with both actors neatly ceding space for the other to monologue before responding in kind. And though the black-and-white 35mm photography is handsome, the actual camera movements and blocking are repetitive, Levinson returning again and again to the same shot/reverse-shot set-ups. Only occasionally does his performance-showcasing approach yield a striking moment, as when he shoots Washington singing and dancing to James Brown’s “Down And Out In New York City” through the window from outside their house, dollying left and right as he triumphantly cavorts in his living room while Zendaya’s character dutifully cooks in the kitchen. Levinson, through Washington, claims that judging a film intelligently means looking at the actual choices made on screen instead of the ones not made “due to an intangible yet purely hypothetical assessment of one’s identity.” But judging Malcom & Marie on such formal grounds does it no favors.

Malcolm and Marie’s fraught relationship history proves so disengaging that Levinson’s fixation on critical reception becomes almost impossible to ignore. Not all of his objections are unfounded. In Malcolm & Marie’s best scene, Marie raises the hypothetical yet believable scenario of Malcolm getting hired to direct a Lego movie, and the waves of hyper-politicized discourse that would follow entirely because of his race. Levinson’s right, too, that some critics fumble with technical language or too narrowly focus on a film’s progressive messaging at the expense of everything else. Yet the sheer amount of time Malcolm & Marie devotes to Malcolm raving about the ineptitude of critics betrays a consuming anxiety. He reserves much scorn for a “white lady from The L.A. Times,” which either refers to a fictional straw(wo)man or real-life L.A. Times critic Katie Walsh. Is it because Walsh gave a negative review to Levinson’s debut feature, Assassination Nation, much like the film’s unnamed critic did to Malcolm’s previous film? Or is it another smokescreen for Levinson to hide behind so that he can insist that critics fall into the trap of assuming intentions they don’t understand? Either way, this petty film puts hoary clichés about critical misunderstanding—updated for the online think-piece era—into the mouth of a character who asserts that Do The Right Thing was revolutionary because it was “made at a time when politics weren’t cool.”

For plausible deniability, Levinson allows Marie to voice objections to Malcolm’s claims, preempting charges of spite under the guise of a self-interrogating internal conversation. Malcolm & Marie is the kind of film that relentlessly comments on itself to create the illusion of self-awareness, when all it does is highlight the weakness of its author’s convictions. No artist is required to respect criticism, but if they’re going to make a film that’s partly about fielding criticism, from the press or one’s partner, then it behooves them to take a stand rather than take every side of a self-generated argument while using artifice as a shield so that no one can tie you to any idea. On the other hand, the meta approach allows Levinson to get ahead of some of his critics. At one point, Marie tells Malcolm not to push away the people who ground him because otherwise he’s “gonna start making fake movies about fake people with fake emotions.” That describes Malcolm & Marie better than any review could.