Game over, man: How Aliens—not Alien—shaped three decades of gaming history

Although the Alien franchise has cast a long and lingering shadow over the world of video games, it was never the lone xenomorph—lurking in the gloom above the Nostromo’s brightly lit corridors, picking its crew off one by one—that would shape the medium in the decades to come. In fact, Ridley Scott’s classic sci-fi horror hybrid was barely registered by gaming at all, at least as far as the first half of the 1980s was concerned. There was a requisite Pac-Man clone for the Atari 2600, sure, and an innovative, if largely forgotten, strategy title for home computers. Together, they added up to a grand total of two official Alien licensed games—the exact number produced by The Dukes Of Hazzard within the same time frame. As influential as it proved for cinematic science fiction, Alien’s methodical game of hide-and-seek between Weyland-Yutani personnel and their deadly stowaway offered little value to an industry whose technical limitations and design mentality favored frantic shooting and platforming over slow-building dread. But then something happened, in 1986: James Cameron delivered his belligerent, cacophonous sequel Aliens, and, faster than the creature’s inner jaw could crack open an overconfident marine’s skull, gaming’s take on Scott’s classic went from borderline abandoned to, well, this:

Video games had mostly ignored the solitary xenomorph, but it was Aliens’ subsequent brood—savage, reckless, and oddly fragile—that made an impact on the medium. The reason was simple enough: In shattering the creature’s mystique, Cameron gave players something to meaningfully point their virtual guns at. His brash, militaristic vision for the franchise superimposed its fantastical conflict over asymmetric combat dynamics, and featured shoulder-strapped heavy artillery, trash-talking mercenaries, and gratuitously exploding antagonists. It reeked of testosterone, transforming a horror icon into a textbook action spectacular—which was exactly what the majority of games were made of in the 8-bit era. But even beyond those early imitators, Aliens’ clawmarks were evident, not just in the sequel’s five official gaming adaptations, but in practically every futuristic shooter for years to come.

Almost overnight, Aliens became a shorthand, a marketing bulletpoint for a gaming landscape that had been losing its sheen as a technological novelty as the 1980s progressed. It was a versatile signifier, too, liberally deployed by games that—apart from a lax approach to copyright law—had little thematic connection to the movies, as cover art, industry-wide, started heavily referencing H.R. Giger’s famous painting Necronom IV. Bosses like R-Type’s memorable Dobkeratops were tailored to evoke the biomechanical horrors of the franchise, while the lush New Zealand archipelago where Contra’s jungle hijinks take place slowly filled up with leering, tooth-filled skulls. The most incongruous instance might be Sega’s Alien Storm, which was basically Golden Axe reskinned as a xenomorph-infested subversion of Eisenhower-era Middle America, the creatures’ embryonic forms hiding under mailboxes untroubled by taggers, while acid-spitting adults pounced at you from behind stacks of cheerfully piled-up consumer goods. Alien had been nowhere in games; Aliens was all around.

Unsurprisingly, the main source of video games’ newfound fascination with the franchise were the inscrutable, deadly creatures themselves. Scott’s impervious stalker might have been snubbed, but Cameron’s hordes provided the medium with adversaries that could be killed in less convoluted ways than individually corralling them to be ejected into the astral void. Consequently—and in addition to free-floating visual references and tacked-on boss fights—there followed a slew of overhead shooters pitting flamethrower-wielding space jocks against a recognizable, if somewhat amorphous, threat: Alien Syndrome for the arcades in 1987; Mastertronic’s exuberantly titled Die Alien Slime a couple of years later; and, more persistently, Alien Breed for the Amiga 500 in 1991, a series that has just kept going, with mobile ports and low-key sequels still available on Steam to this day. Side-scrollers were equally well-represented, with Trantor: The Last Stormtrooper and Xenophobe’s anxious corridor-roamers hitting the stores barely a year after Cameron’s sequel arrived in theaters.

While the tide of 2D shooters riffing on the Aliens premise started receding in the early ’90s, the xenomorph’s distinct anatomy had irrevocably imprinted itself on the industry’s design lexicon. In a 2014 interview, John Romero recounted how the original Doom team kept Giger’s Necronomicon “open in front of them, to help them come up with crazy disturbing stuff.” As the millennium drew to a close, Starcraft unleashed the strategy genre’s most infamous race of people-eating bug monsters—yet the Zerg in general, and the towering Hydralisks in particular, are inconceivable without the Alien franchise as inspiration. And more recently, Arkane’s extraordinarily immersive Prey modeled the escalating Typhon threat aboard Talos I roughly along the lines of a xenomorph’s stages of growth: The bursting Cystoids crowding the station’s zero-gravity passageways are akin to the eggs first discovered inside the wreck on the surface of LV-426. The cephalopod-shaped Mimics demonstrate a penchant for catching scientists off-guard before attaching themselves to those poor souls’ faces. And the hulking Nightmare presents a nearly indestructible adversary, not unlike Cameron’s ultimate adversary, the alien queen.

The creatures’ physiology was hardly the only aspect that video games scoured for inspiration, either. Once Aliens opened the floodgates, the series’ striking set design proved just as influential, both the sterilized corridors of the Nostromo, awash with cold light; and the tenebrous, womb-like chambers occupied by the creatures themselves. Notable examples of the former include Project Firestart, arguably the first fully formed survival horror title (and one which we’ve already visited in some depth), and the futuristic RPG brazenly titled Xenomorph by a British publisher, Pandora, that was clearly unconcerned about the prospect of litigation. The latter game lifts not just the opening from both movies with an interrupted bout of cryosleep, but also the morgue-like glare and austere spatial organization of Weyland-Yutani ship architecture, as you investigate the eerily lifeless hallways of Atargatis station to discover what became of the roughly 200 residents supposedly awaiting your arrival.

And while action was the first genre to fall in love with this franchise, slower genres proved even more ideally suited to exploring these environments in detail. It’s no surprise, then, that a puzzle-shooter like Cybernoid II decorated each room of its metallic maze with a tapestry of living tissue and ooze-dripping body parts, including an assortment of reptilian, fang-filled heads. Point ‘n’ clicks were an even better fit, with 2015’s Stasis convincingly capturing the unsettlingly biomechanical nature of alien-infested territory. The Brotherhood’s gorgeous isometric adventure sees protagonist John Maracheck waking aboard an unfamiliar spaceship where whole sections are covered by congealing bodily fluids, passageways are blocked by pulsating pods, and faulty lighting means that wall-protruding cables are barely distinguishable from moving tendrils. Cyberdreams went a step further two decades earlier by enlisting Giger himself for the backgrounds for its horror adventure title Dark Seed—or, at least, persuading him to lend them some of his lesser known works to slap up as set dressing. The game’s manual, filled with cheerily enumerated technical details of its development, hints at a difficult collaboration with the Swiss artist, who demanded the use of an unusual high-resolution mode and, eventually, a sequel. The result, however, was an adventure still remembered three decades later, if only for its visual prowess, rather than typical genre hallmarks like narrative or puzzles.

Nevertheless, it was a more traditional action title that most famously (and effectively) drew inspiration from Scott and Cameron’s sets. While Dead Space’s Lovecraftian overtones bring it closer to cult classic Event Horizon, both its grotesque enemies (cheekily called “Necromorphs”), and the claustrophobic architecture of the USG Ishimura, owe clear and obvious debts to the Alien franchise. A profoundly well-crafted third-person shooter buoyed by sublime audio design, Dead Space is a game where every attack carries wince-inducing heft, and every fragment of exposition strikes a perfect balance between painting a harrowing story, and allowing trigger-happy players to promptly resume its glorious dismemberments. (Essentially, it manages to combine the cat-and-mouse game of Alien with the rip-roaring violence of its sequel.) Still, the core appeal in Isaac Clarke’s saga lies in the way the Ishimura’s labyrinthine environments are exploited to create an atmosphere of unease. This tension stems from both a purely aesthetic level, with blood and viscera smearing the vessel’s perpetually underlit corridors, and from the more immediate survival concerns raised as sharp corners and billowing steam impair visibility, cramped spaces offer little room for maneuvering or escape, and numerous air ducts double as potential ambush sites.

Finally—but no less pervasively—is the character archetype Aliens bequeathed pop culture in general, and gaming in particular: the humble, hard-ass space marine. Jenette “Vasquez” Goldstein’s military-casual look has dictated the ways developers have been accessorizing their soldiers for decades, from the loose, sleeveless shirts of Contra’s dynamic duo, to the looks adopted by Gears Of War’s burly bug fighter Markus Fenix. In fact, Gears owes a special debt to Aliens, not just as a source of inspiration for its antagonistic Locust Horde, but in terms of squad dynamics and the diction of its COG characters, with Damon Baird’s abrasive sarcasm frequently channeling the film’s Pvt. William Hudson. Whether adhered to, as in the Epic Games blockbuster, or subverted, as in Bulletstorm’s outrageous banter, the template for the hard-as-tacks, unruly, but ultimately heroic space commando was outlined in 1986, and has informed gaming ever since.

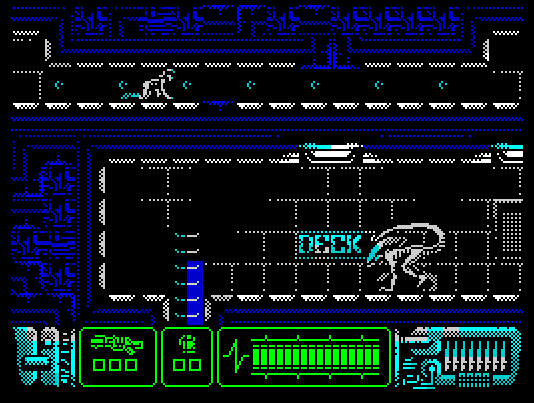

Whether for enemies, protagonists, or environments, the Alien franchise has been extensively mined and weaponized for inspiration over the last three decades of video gaming success. Ironically, the unauthorized homages have done far more to shape the medium than any official adaptation of the series, of which only a couple have been truly memorable. (Most notably: An enjoyably silly arcade beat-em-up from 1994, Wayforward’s shockingly good Aliens Infestation for the Nintendo 3DS, and 2014’s Alien: Isolation—which broke with franchise tradition by explicitly attempting to ape the rhythms of Scott’s film, not Cameron’s.) Apart from the big-budget entries—your Gears and your Halos—there’s been a constant stream of indie and retro sci-fi-action efforts exploring different facets of the franchise for the better part of the last 30 years. In 2016, space-scavenging sim Duskers employed its security-camera aesthetic to maximum effect, understanding that nothing is as terrifying as the sound of an airlock opening in the next room of a supposedly derelict ship. Browser game Alien Harvest generated tension by charging you with collecting a number of alien eggs strewn across its maze-like forests before they hatch into hungry adults. And last year’s Aliens: Neoplasma emerged as a supremely polished return to the ZX Spectrum’s limited palette, and the side-scrolling shooters of yore.

After successful transforming the nature of the threat from outer space—from something cold and mechanical swooping from the skies, to something live and slithery lurking in the dark—Aliens’ infestation of video gaming show no signs of slowing down. If you thought your future space marines were going to find peace in a galaxy free of their threatening presence, well, in the famous final words of one Weyland-Yutani android: “I can’t lie to you about your chances. But you have my sympathies.”