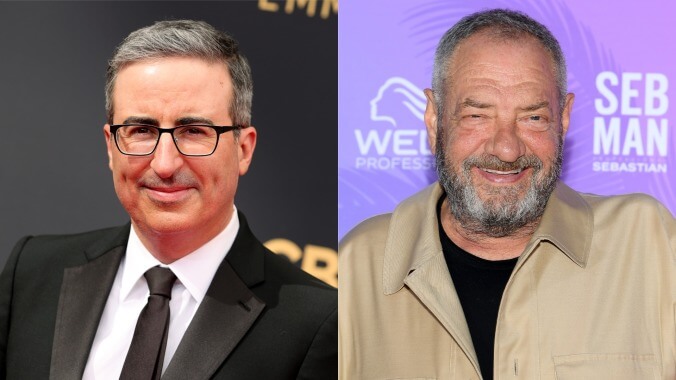

John Oliver has more than fair criticism for Dick Wolf over Law & Order's unrealistic world

“Law & Order is never going to grapple with the reality of policing in a meaningful way,” Oliver says in last night's episode of Last Week Tonight

In the criminal justice system, the people are represented by two separate yet equally important groups: the actual criminal justice system and how Dick Wolf thinks it works, or should work. Actually, scratch that—one of those groups is a filmed fantasy and the other is one of America’s most consequential government systems. More often than not, as John Oliver points out in Sunday’s especially apt episode of Last Week Tonight, Dick Wolf’s world and the real world exist in total opposition to each other.

In an episode discussing Law & Order, Oliver takes aim at the longstanding franchise’s depiction of the justice system, stating that the series “makes a lot of choices that significantly distort the big picture of police.” Oliver also notes that Wolf, the series creator, has historically maintained a “close, behind-the-scenes relationship with the NYPD, employing officers as consultants and boasting about the access he had.”

“Law & Order is never going to grapple with the reality of policing in a meaningful way…” Oliver says. “Because fundamentally, the person who is responsible for Law & Order and its brand is Dick Wolf.” Wolf has previously described himself as “unabashedly pro-law enforcement.”

Oliver also cites an old interview where Wolf explains that Law & Order’s purpose isn’t to “do Abner Louima,” a Black man who was sodomized and beaten by NYPD officers in 1997.

“That’s a terrible thing that happened, but that represents one or two bad apples in a police force of 35,000 people,” Wolf says, parroting a classic pro-policing argument that begs the question: can one really compare a few bad apples to one enormous, systemically violent orange?

Per Oliver, many of Law & Order’s problems stem from the fact that the reality of policing in America would be “unwatchable” for most audiences. “Nobody wants to watch a show where 97 percent of episodes end with two lawyers striking a deal in a windowless room and then you get to watch the defendant serve six months and struggle to get a job at their local Jiffy Lube,” he asserts.

Oliver also cites the endless stream of wealthy, white defendants in the series, a writing decision that Wolf has explained in interviews by stating “there are no rich-white-guy pressure groups. You can do anything you want to rich white guys and nobody cares.” What that mentality accomplishes, Oliver argues, is that “instead of depicting a flawed system riddled with structural racism, the show presents exceptionally competent cops working within a largely fair framework that mostly convicts white people.”

In conclusion, Oliver argues that Law & Order plays like less of a crime series and more like an advertisement for police. But unlike the stream of good-guy cops on the series, Oliver asserts that Law & Order fails in capturing its “defective” subject. In Wolf’s warped onscreen world, Oliver says, “the cops can always figure out who did it, defense attorneys are irritating obstacles to be overcome, and even if a cop roughs up a suspect, it’s all in pursuit of a just outcome.”