Last Call BBS, its creators' final game, is a love letter to the process

The last game from Zachtronics is a treatise on the pleasures of making something small and perfect and strange

Every Friday, A.V. Club staffers kick off our weekly open thread for the discussion of gaming plans and recent gaming glories, but of course, the real action is down in the comments, where we invite you to answer our eternal question: What Are You Playing This Weekend?

The Zachtronics catalogue is a clearinghouse of beautiful machines that do not exist: The elegant alchemy engines of Opus Magnum, the tiny conceptual robots of Exapunks, the sprawling, played-created contraptions of Infinifactory. And especially the computers—the utterly fake, lovingly rendered machines that pop up throughout creator Zach Barth’s work, from the visually barebones TIS-100, through the various machines that dot Shenzhen I/O, all the way up to the Sawayama Z5 Powerlance that exists at the heart of Last Call BBS, apparently the final full game Zachtronics will ever release.

Zachtronics titles are niche games for niche people; puzzle games for would-be computer programmers of fictitious computers, who thrive on a world where the player is given the absolute bare minimum of information (and sometimes a little less) required to solve the problems in front of them. “Here are (some) of the rules,” Barth’s games tell their players. “Figure out the rest yourself.” (Is it any wonder that Barth’s early hobby game Infiniminer would, through a convoluted series of events, become the prime inspiration for Minecraft, one of the ultimate expressions of emergent gameplay in modern games?)

In that context, Last Call BBS is textbook Zachtronics: Players are gifted a copy of an old Powerlance, running an emulated version of an old school bulletin board, filled with pirated games that just happen to play like some of Zachtronics’ greatest hits. (So, yes, you’re playing fake games from a fake bulletin board being emulated on a fake computer; the meta headrush is a feature, not a bug.) As you solve the various puzzles, you get drips and drabs of story from the person who gifted you the computer, a melancholy tale of youthful enthusiasts slowly aging past their greatest ambitions.

It’s probably not a coincidence that Zachtronics has released a game that’s all about accepting the limits of game development as a process, just as the company itself is closing up shop. (You can read an interview with Barth about the news over at our sister site, Kotaku.) With its loving recreations of old warez crack screens and tiny stories of stunted ambitions, Last Call is no grand narrative or sweeping statement; instead, it’s a celebration of the muted pleasures of making something strange and personal, and then letting it float out onto the internet, where the sum total of your reward is usually the vague knowledge that someone, somewhere, is hopefully enjoying it.

So if there’s a sense, in some of the mini-games that make up this collection, of treading water, or playing the hits, well—call that both a practical and a philosophical concession. (Barth himself notes, in the above interview, that the company has struggled to make games that work outside its “programming fake computers” niche, which gets a little old after 12 years on the job.) And yet the old highs are still there: Of bending your brain around corners made of code, of hunting down the epiphanies that can only come from navigating an invisible maze. (Very literally, in the Sudoku riff Dungeons And Diagrams, the most accessible, least Zach-ish game in the collection.)

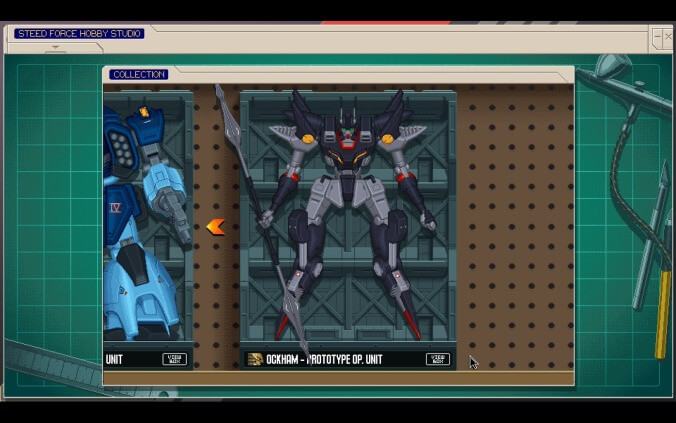

The most telling expression of the game’s whole ethos, though, actually comes from a portion of Last Call BBS that barely even qualifies as a game at all: Steed Force Hobby Studio, a fake model building simulator for a fake anime series hosted on a fake, etc., etc., etc. More than anything else in Last Call, SFHS—with its meticulous snipping of virtual plastic, and the satisfying CLICK as pieces come together—is a celebration of process, of the joys of just making something, commercial impact or algorithmic appeal be damned.

“I was just so impressed,” the in-game character writes, when explaining why this non-game was included in the grab-bag of programming titles on their virtual BBS, “By the lengths this guy went to of making all this art and everything, and releasing it all for free just because he wanted to build some model kits with his kid … I think that’s such a great expression of the creativity of that early computer era. There weren’t nearly as many rules or commercial pressures. You could just make a fun toy, and that was the whole point.”

Last Call BBS is available on GamePass and Steam; the rest of the company’s brilliant, frustrating, beautiful clockwork collection of games is also still readily available for sale.