Pentiment is a brilliant game about being a terrible medieval murder-solver

Obsidian's gorgeously illustrated new game owes as much to The Name Of The Rose and neo-noir as it does traditional mystery stories

Every Friday, A.V. Club staffers kick off our weekly open thread for the discussion of gaming plans and recent gaming glories, but of course, the real action is down in the comments, where we invite you to answer our eternal question: What Are You Playing This Weekend?

[This article contains spoilers for the first act of Pentiment.]

I watch the executioner’s blade fall. It doesn’t cut clean; the condemned monk falls forward in obvious agony, beautifully sketched blood pouring from the wound in his neck. Another hacking cut, then a third, and finally the head of the convicted murderer rolls free, its face frozen in an artfully rendered expression of pain. I had the option to look away from the carnage, a few moments earlier, but I didn’t take it. After all, I was the reason this innocent man was dying a murderer’s death.

Pentiment snuck up on me. After two straight games (the decidedly lackluster Outer Worlds, and then the simply-not-for-me Grounded) that suggested that studio Obsidian was drifting further and further away from the sorts of word-nerd games (Fallout: New Vegas, the broken and brilliant Knights Of The Old Republic 2, and, most recently, 2016's Tyranny) that had made me fall in love with it, I was hesitant to trust again. The art style—modeled, with incredible ingenuity, on the look of the illustrated manuscripts of the game’s 16th-century setting—certainly appealed. The conversations I’d seen people have about the game’s gorgeous fonts intrigued me. But it wasn’t until I learned that the core of the game was a murder mystery, set in a medieval Bavarian monastery, that I realized I needed to play it.

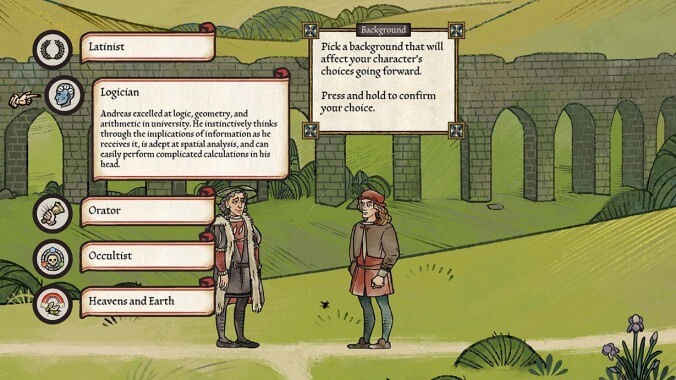

I was hooked from the jump, as the game immersed me in the world of tiny Tassing, a village built around the fading Kiersau Abbey, where my character, journeyman Andreas Maler, was temporarily working as an artist. I hummed happily at the game’s character creation, picking those traits—a logical mind, a bit of medical knowledge, a grounding in rhetoric, French, and Italian—that I thought would aid me in the investigation I knew would inevitably break out. And, in the meantime, I simply enjoyed the game’s art, and also its writing, which spoke about sometimes obscure topics in relatable ways that allowed warmth and character to shine through. And then, of course: The murder!

But something happened as I employed the standard implements of the detective game’s toolkit—autopsy, interrogation, investigation, subterfuge, deduction, and more. The ticking clock hanging over the death of a local noble began putting more and more pressure on me, and on Andreas. Choosing a likely suspect, I began devoting more of my limited resources to investigating this man, burning whole precious afternoons pursuing my hunch. The digging (sometimes literal) paid off: The day before the judge was to arrive in Tassing, ready to pass immediate sentence on the most likely culprit, I had a motive, murder weapon, and opportunity all lined up.

And then, during a chance meal with some of Tassing’s less privileged townsfolk—those meals being a recurring feature of the game’s scheduling, allowing for information gathering and gorgeously rendered versions of period-accurate foods—a traveler casually mentioned seeing something that blew my entire theory out of the water. I suddenly knew that my prime suspect was almost certainly innocent…and that I had an afternoon, at most, to try to put together an alternate hypothesis, with evidence to back it up.

I tried. I really did! I tugged at threads. Re-thought certain conversations. Looked for new motives and examined certain clues in new light. I got far enough to have a decent guess at what might actually have happened—but as the archdeacon arrived in town to pass judgment, ready to hand out the demanded death necessitated by a noble murder, I knew I didn’t have the juice to actually prove my new theory. And if I couldn’t prove it, Andreas’ kindly mentor—the chosen scapegoat for the killing, if no more likely candidate could be put forward—would be executed for the crime.

I didn’t lie, okay? I didn’t invent one single fact, as the tribunal put its full attention on Andreas, aware that he had been investigating the murder with some diligence. Instead, I simply presented the evidence I had dutifully collected—evidence that I knew would condemn my first suspect, an innocent man, to death. What else could I do?

Pentiment takes, as its most obvious influence, Umberto Eco’s 1980 historical detective novel The Name Of The Rose. (It’s actually one of several games, most of them produced in Europe, that have either directly adapted, or heavily referenced, Eco’s book; it’s a strange little sub-genre of interactive fiction.) And, like Eco’s novel—where Holmes-esque friar William of Baskerville, for all his cleverness and logical acumen, inevitably causes far more damage and destruction by investigating a crime than he would have by simply leaving well enough alone—it’s a story in which a would-be detective wandering into a crime is far more likely to be a force of chaos than one of justice. I have solved a lot of murders in video games at this point, unraveled god knows how many insidious plots, and come out the intellectual victor. Few of those triumphs have ever affected me as much as watching a man who I’d condemned to an unjust fate scream his innocence, even as that first horrible blow fell.

Pentiment is an artful game, in multiple senses of the word. Even when you think you’ve become inured to its striking visual style, it’ll pull some trick—an allegorical dream sequence, or a trip traipsing through the illustrations of a literal storybook—to remind you of the beauty of what you’re looking at. But it is, if anything, even more artful in the way it tells its story. Both Andreas and I had the best of intentions when we set out to solve a murder. We did the most we could with the limited time and resources available. And then we failed, in ways that left long-lasting wounds on an entire community. For a genre that so often celebrates cleverness for the sake of cleverness, it was a sobering and, yes, an artful reminder of the limits of what good intentions can achieve—and the full breadth of the horrors they can inflict.