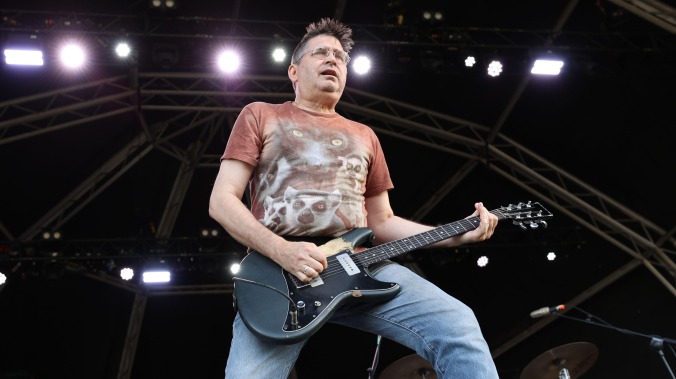

R.I.P. Steve Albini, Nirvana engineer, Shellac frontman, and architect of American Independent music

The prolific recording engineer of The Pixies and Nirvana was 61

Steve Albini, among the most influential and respected figures in American independent music, known for producing Nirvana, The Pixies, and his bands, has died. As confirmed by the staff of his recording studio to Pitchfork, Albini died of a heart attack. He was 61.

It’s hard to overstate Albini’s impact on American underground music. First as producer in the revolutionary electronic punk band Big Black and later Shellac, and, of course, as the producer of some of American punk’s most iconic albums, including Nirvana’s In Utero, The Jesus Lizard’s Goat, and The Pixies’ Surfer Rosa. His ability to capture the booming drums with such deep lows and guitar heroics with screeching highs in a comprehensible package, harnessing the power and fury of its players, became the blueprint for D.I.Y. home studio enthusiasts and basement record producers worldwide.

The provocative contradictions of his work are evident in Albini’s upbringing. Born on July 22, 1962, in Pasadena, California, Albini escaped the site of the future L.A. punk explosion by moving with his family to Missoula, Montana. As Black Flag gained momentum in the shadow of his former home, Albini nursed a broken leg and learned to play bass. He also heard The Ramones for the first time. “The Ramones changed the way I thought about music, and therefore, the rest of the world,” Albini said in 2020. “The Ramones implied to me that there was a different way to live and a different way to see the world, and I wanted to be a part of that.”

Albini quickly fell into the burgeoning punk music scene the Ramones would inspire, an interest leading him to Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, where he assumed an active punk scene must thrive. The Chicago underground music scene invigorated Albini, who began playing in local bands and contributing to fanzines.

In 1982, he released Lungs, the first EP from his band Big Black. Creating some of the most antagonistic, hostile, and offensive music of punk’s first wave, Big Black cut through the uniformity that began infiltrating the genre’s independent beginnings. With the help of a drum machine on the verge of a nervous breakdown and piercing guitars turned to ear-bleeding volumes, Big Black turned Suicide’s electronic yearning into hate. Songs about rape, child molestation, racism, murder, and violence against women littered Big Black’s discography, often making the subject of controversy and outcry. The band’s swan song, Songs About Fucking, would become its most successful work. Albini’s acerbic assault on the listener would give the likes of Trent Reznor and Kurt Cobain the runway to go darker and more violent and experimental.

Following Big Black’s demise, Albini formed the ill-fated Rapeman with the members of fellow noise rock enthusiasts Scratch Acid. Unsurprisingly, the name “Rapeman” did not go over well with American audiences, inspiring protests and negative media attention. Albini contended they took the name from a Japanese comic book character but later expressed regret for this and other early provocations, of which there were many.

“I certainly have some ’splainin to do and am not shy about any of it,” Albini explained in a viral 2021 Twitter thread. “A lot of things I said and did from an ignorant position of comfort and privilege are clearly awful and I regret them. It’s nobody’s obligation to overlook that, and I do feel an obligation to redeem myself.”

“A project I’ve undertaken piecemeal as I’ve matured, evolved, and learned over time. I expect no grace, and honestly feel like I and others of my generation have not been held to task enough for words and behavior that ultimately contributed to a coarsening society […] I’m overdue for a conversation about my role in inspiring ‘edgelord’ shit. Believe me, I’ve met my share of punishers at gigs, and I sympathize with anybody who isn’t me but still had to suffer them.”

While Albini was known for putting his foot in his mouth on more than several occasions throughout his storied career, it never scared off collaborators. Always credited as “recording engineer,” not “producer,” Albini worked with some the most influential and respected names in rock, including PJ Harvey, Godspeed You! Black Emperor, Neurosis, Jawbreaker, Joanna Newsom, Superchunk, and The Stooges. One only needs to look at his output between 1986 and 1989 to gauge his potential, with credits on Pixies’ Surfer Rosa, Urge Overkill’s Jesus Urge Superstar, and Pussy Galore’s Dial ‘M’ For Mother Fucker. Albini’s ‘90s would eclipse even that.

Much to his chagrin, the grunge explosion from Seattle had made the types of records Albini wrote and recorded profitable and mainstream. Despite not thinking much of Nirvana, Albini agreed to record their Nevermind follow-up, In Utero, inviting the band to indulge the darkness Kurt Cobain so evocatively and poetically expressed. Cobain, a student of SST and Touch and Go Records, found a common cause in Albini’s blend of controlled distortion as Albini shepherded the band down more complex and unpredictable avenues. 1993’s In Utero became a sterling example of Albini’s mastery, grinding punk’s discordant notes while making sharp as a Ginsu knife, leaving a wound that reopens every time “Heart-Shaped Box” plays.

In Utero helped grow Albini’s reputation, and he began attracting even bigger acts, such as Jimmy Page and Robert Plant of Led Zeppelin. Yet he continued to record local punk bands and those on the fringes of the American underground. Throughout the 2000s, Albini remained at the forefront of independent music as a vocal critic of the industry and a primary character in its creation, attracting many names that defined the last two decades of D.I.Y. indie rock, such as Sunn O)), Ty Segall, and Screaming Females.

In recent years, Albini reunited with his post-Rapeman band, Shellac, the group he shared with fellow recording luminary Bob Weston. The band’s sporadic schedule kept them creeping into the Touch and Go catalog roughly twice a decade, offering a new album and reunion tours. Their final album will be released on May 17, 2024.

Steve Albini’s work has left a visible scar on rock music, making a solid case for analog recording in an age of digital dominance. The warmth people say can be heard on vinyl records can be heard on every one of Albini’s productions, replete with bottomless low-end and crackling overdrive. Relying on copious amounts of mics, minimal overdubs, and groups willing to withstand searing criticism from their engineer, his work sounds like people playing music in a room together. In the end, that’s what it was, and Albini captured it.

He is survived by his wife Heather Whinna.