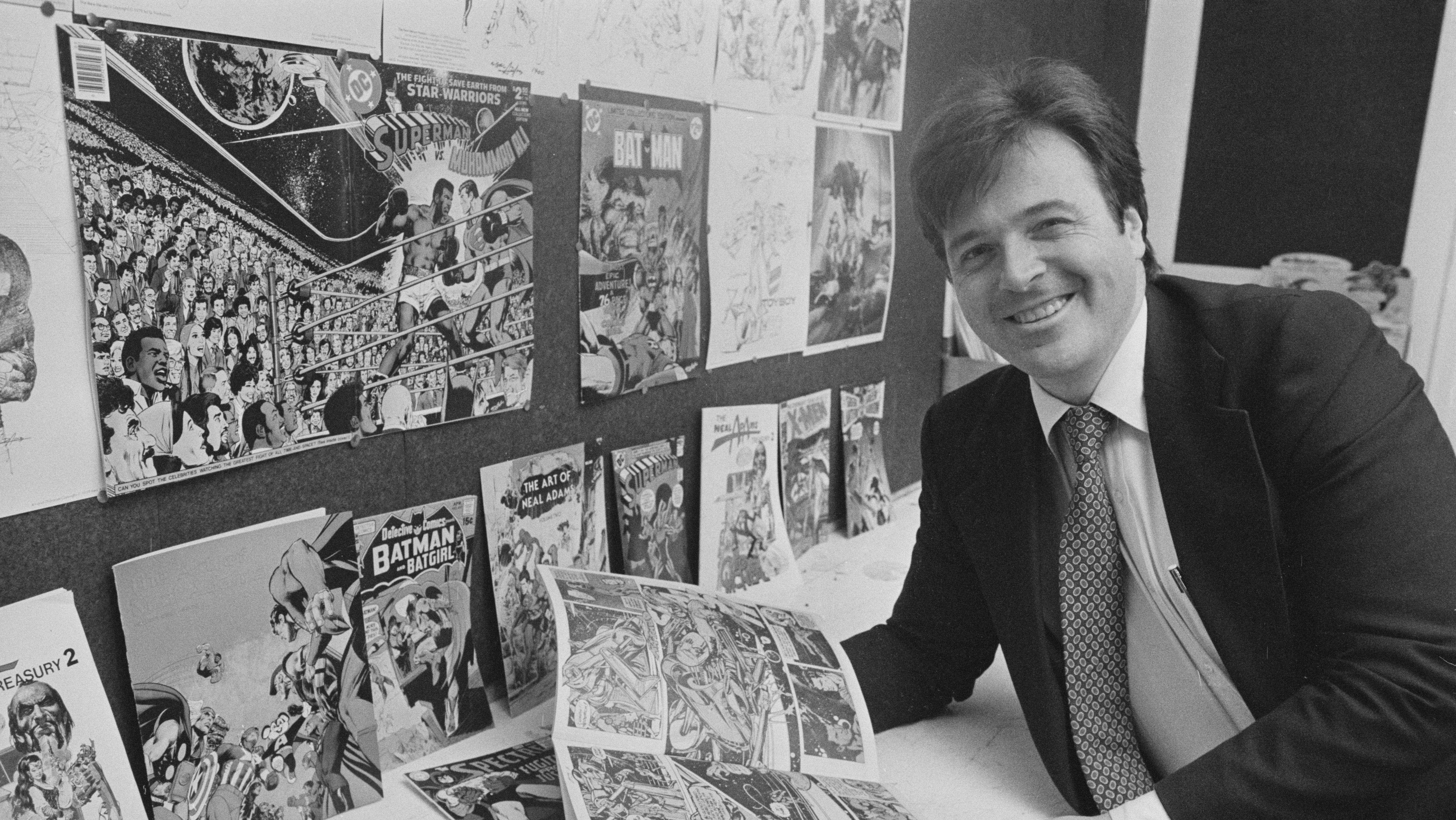

R.I.P. legendary DC Comics artist Neal Adams

Adams' version of Batman in the 1970s set the scene for a million dark and brooding takes on the iconic character

Neal Adams has died. A long-time artist best known for his legendary, character-creating and -defining runs on DC Comics—and for his work as an advocate for comics creators’ rights—Adams defined the looks of whole eras of the history of some of the most iconic characters in the medium. Characters he left a lasting impact on include Green Lantern, Green Arrow, and especially Batman—whose modern incarnations owe much to the brooding, shadowy take on the Dark Knight that sprang out of Adams’ run on the character during the first half of the 1970s. Per THR, Adams died yesterday morning, at the age of 80, from complications of sepsis.

Adams got his start in comics straight out of high school, with his persistence landing him a gig drawing, for a time, humor books at Archie Comics. The next few years would see him dip in and out of various branches of the professional illustrating world throughout the 1960s, drawing newspaper comic strips, illustrated advertisements, horror comics, and more. But his eye apparently never strayed far from the first company he’d ever reportedly applied to work for: DC Comics.

When Adams first got his break at the company, it was decidedly not on high-profile superhero books; he instead spent the first part of his tenure there doing war comics, licensed Jerry Lewis books, and other non-cape material. Finally, though, he broke in to superhero work as a back-up and cover artist, finally getting a chance to draw the character he’d been angling for all this time—Batman—for a cover in 1968.

In the meantime, Adams picked up his first serious fan attention for his work on a less well-known hero, Deadman. (A.k.a. Boston Brand, a ghost capable of possessing mortals to do good deeds.) Adams took over the character’s art, and then scripting duties, for his self-titled series in the late 1960s, impressing readers with his dynamic use of body language and shadow. It was the beginning of a rise that would see him become one of the most respected artists in the industry, with his work spearheading an increasing understanding of comic book art as art, rather than as a mere vehicle for superhero stories.

All of that came to a head a few years later, when he and writer Dennis “Denny” O’Neil came together on Batman in the early 1970s. The O’Neil/Adams run was, in some ways, a direct reaction to the Batman of the 1960s, which had embraced the campy elements of the character so prevalent in the hit Adam West television show. But rather than purely reactionary, the pair’s take on the character was also formative: A re-understanding of the character as a grim avenger who stalks a crime-corrupted and shadow-drenched city, facing off against ageless assassins and sociopathic murder clowns. (O’Neil and Adams invented, among other characters, Batman antagonist Ra’s al Ghul; they didn’t invent the Joker, obviously, but later interpretations of the character are so indebted to the pair’s “The Joker’s Five-Way Revenge” that they pretty much might as well have.)

O’Neil and Adams also re-imagined the fairly minor characters Green Lantern and Green Arrow during this same period, creating one of the strangest superhero comics of the 1970s in the process: Green Lantern/Green Arrow, which saw the pair roaming America, directly addressing societal problems—most notably the reveal the Green Arrow’s sidekick, Speedy, was addicted to heroin. These “relevant comics” can look cheesy to modern eyes, admittedly, but they were also an outgrowth of Adams and O’Neil’s convictions that superhero comics could interface with, rather than ignore, the politics of the era in which they were published.

Adams, never politically shy, used also used his growing reputation to disrupt systems inside the comics industry that put much of the power in the hands of publishers. He openly freelanced for both DC and its rival Marvel in the late ’60s—generally frowned at by the publishers—contributing art to a run on X-Men. He also became an open advocate for creators rights; among other things, he was one of the loudest voices in the industry calling for the return of original artwork to creators, and specifically for DC to acknowledge the contributions of Superman creators Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel for their massive impact on the company. He also founded his own studio, Continuity Associates, which provided storyboard artists for Hollywood films—in part, to give professional illustrators an outlet for their talents beyond DC and Marvel.

As the 1970s gave way to the 1980s, Adams settled into more of an elder statesman role, although he also continued to draw regularly. (His final series for Marvel or DC came in 2020, a Fantastic Four book he drew for Mark Waid.) He devoted his later attention to a variety of causes, some (comics rights; working to explore the history of the Holocaust) less esoteric than others (his repeated belief that the Earth was expanding, which he often called in to radio conspiracy show Coast To Coast to promote). But he remained, and remains, one of the gods of 20th century comics; an artist who didn’t just define the look of superhero comics, but also pushed back on assumptions of how the industry itself could, or should, run.

DC Comics penned a tribute to Adams earlier today, writing, “With deep respect for Neal and his tireless work and great love for the comics industry, we extend our condolences to his family and friends.”