pioneer looking back at his life through the same sort of high-flying window that his various strategy games and flight simulators have used as their entry point into virtual worlds for the better part of 40 years. Dispassionate and detached, Meier’s book is the sort of memoir that reveals more about its subject through omission than outright revelation—as when new Meier offspring suddenly pop up in the narrative of the designer’s life apparently out of nowhere, alongside far more detailed accounts of the releases of his numerous games.

Which, to be fair, is probably what anyone cracking open a book about Sid Meier’s career is looking for; as the man himself would (and does, at several points in the text) admit, the actual details of his life are almost relentlessly, intentionally dull. The text itself—written with Jennifer Lee Noonan—is lively enough, though, full of game design tidbits, and employing a clever running gag with footnoted achievements mimicking those you’d find in any AAA video game of the last 15 or so years. Meier’s apparently indefatigable reserves of, uh, reserve don’t stop him from giving the people what they presumably want either. The veteran designer talks about Civilization’s infamous “Nuclear Gandhi” meme. (The story about it being caused by a memory bug is apparently a total fiction, by the way.) He swaps stories about the early days of running his first games company, MicroProse, alongside far more flamboyant former fighter pilot William “Wild Bill” Stealey. He talks about his famous maxim that labels games as “a series of interesting choices.” To some extent, Memoir!—its name itself a reference to the titling tropes of Meier’s games, and the way he eventually became one of the industry’s first (literal) name brands—could just as accurately be titled Sid Meier Plays The Hits.

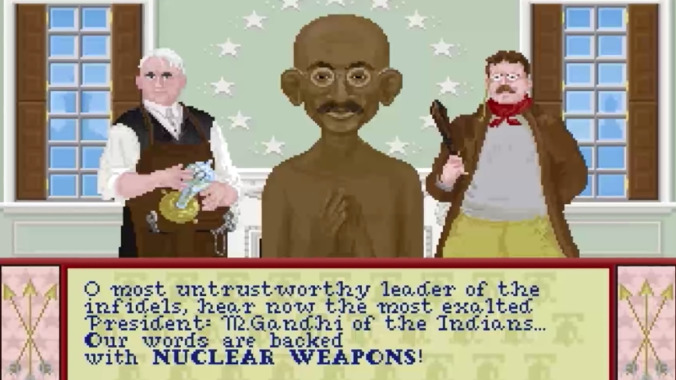

What it lacks—almost to the point of pathology—is a willingness to indulge in introspection about the actual contents of the games Meier spent his career sticking apostrophe-esses on. By its very nature, Civilization was a radically political game when it arrived to slowly growing acclaim on computers in 1991, asking players to contemplate what “success” looks like for generation-spanning regimes, and imposing its own ideas about realpolitik onto the people playing it. (Gandhi likes to brag about his nuclear arsenal, Meier explains, not because of a bug, but because he’s programmed to avoid war—and in Civ logic, threats of mutually assured destruction are the swiftest path toward peace.) This is heady stuff for a 37-year-old game designer to stumble backwards into while trying to create one of the most ambitious video games of all time, and Meier’s older self deals with it all by assiduously not dealing with it. The closest he comes to actual contemplation of the assumptions underpinning much of Civilization’s political design is an extended paragraph discussing the decision to remove Nazi Germany from the game in favor of a German empire under Frederick The Great. And even then, it’s couched in terms of not wanting to get yelled at, more than an actual stance on the merits of various world leaders as playable characters. (As he notes, nobody even blinked at the inclusion of Mao or Stalin in that same initial grouping of “great” leaders.)

What makes this even more fascinating and/or frustrating is when it’s taken in comparison to the only passage in the book where Meier does appear to get genuinely emotional or pissed off: a description of the moment when he looked over Brian Reynolds’ Sid Meier’s Civilization II—despite the masthead, Meier never served as lead designer on any Civilization game after the first—and found that the game included a “cheat” menu. “Cheating was an inherent part of the game now, right on the main screen?” he writes, aghast. “This was not good.” Although Meier eventually admits that modding, and other tools that give players more control over the experience of playing the games they ostensibly own, helped propel the series into decade-spanning longevity, his initial gut reaction is the one moment in the book where it feels like the real Sid Meier, professional game designer, pokes through the genial fog in which he seems to live most of his life. In arguing that it’s the designer’s job to “protect” players from their own desire to take the easy way out of problems, Meier reveals a design philosophy that runs through his games just as aggressively as anything about respecting player choice. The designer writes about encouraging or even forcing players to play the “right” way—even as he eventually admits that his belief that players needed to be kept safe from “damaging their own experience” via modding was totally wrongheaded.

Meier—at least, the Meier of the past—seems to view the relationship between designer and player as an inherently adversarial one. His goal as a designer, then, is to craft a game that prods the player into playing in the “correct” way above all else. Is it any wonder, then, that he couldn’t see the nuclear forest for the ICBM-shaped trees, creating a world in which the only way for Gandhi to keep war at bay is by gloating about the oncoming nuclear fireball? The idea of “Nuclear Gandhi” was never meant to be an intentional part of Civilization’s game design. But what Sid Meier’s Memoir! makes clear is that it was, nevertheless, the product of a clear and purposeful intent.