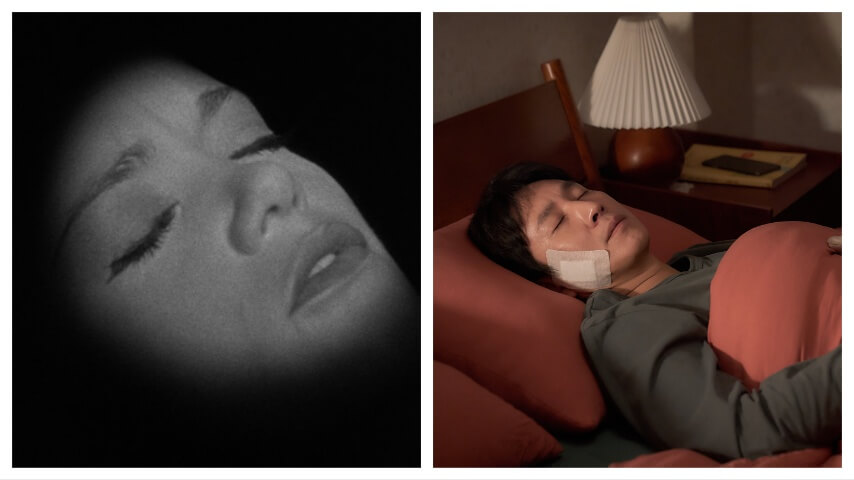

Sleep throws back to the mysterious horror impulses of Cat People

The Korean fest hit delves into the unconscious terrors dwelling in our bodies,

Image: Criterion Collection; Lotte Entertainment

Shirley Jackson once wrote in her journal: “who wants to write about anxiety from a place of safety? although, i suppose i would never be entirely safe since i cannot completely reconstruct my mind.” That verb “reconstruct” is an apt one for Jackson, whose most famous novel The Haunting Of Hill House follows characters stuck in the winding, shifting halls of a haunted mansion. Over the course of that narrative, the house is portrayed as something alive, beating and warm and ugly—being lost in it is like being trapped in someone’s mind, or locked in someone’s body.

That idea—that we could spend years blindly feeling out the shadowy corridors of our own bodies, only for them to remain fundamentally unknowable—is the basis of Jason Yu’s feature directorial debut Sleep. It’s the middle of the night and a heavily pregnant Soo-jin (Jung Yu-mi) is shifting restlessly; her husband Hyun-su (Lee Sun-kyun) is sitting upright, muttering something in his sleep. But soon the horror narrative unfurls, ominous bangs and thumps emanating from their apartment. From there Soo-jin witnesses her husband descend further into sleep-addled madness, raiding the fridge of raw meat and leaning out of open windows. Hyun-su’s first sleep-talking utterance, “someone’s inside,” takes on more meaning as Sleep progresses—a detriment to the sense of unspecified foreboding plaguing Soo-jin in that first act.

Jacques Tourneur’s provocative 1942 thriller Cat People is similarly obsessed with that slippery idea of safety, and is a film that fails to settle on a single kind of evil, arguing that the real villain is something less definite, more intrinsic to our biology. As such, it’s no coincidence that the first voice heard in the film is Cat People’s resident psychiatrist, Louis Judd (Tom Conway), a character tasked with untangling people’s complex inner evils. His opening quote says, “Even as fog continues to lie in the valleys, so does ancient sin cling to the places, the depressions in the world consciousness.”

Cat People is about the fog that clings to each person, destabilizing the landscape of married life—in Jackson’s words, Cat People is not written from “a place of safety,” relishing its dangerous outlook. Cat People follows the alluring Irina (Simone Simon) and eager Oliver (Kent Smith) as they embark, ill-equipped, into marriage, despite her dark secret: Sex is off the table for these newlyweds, held at bay due to Irina’s assumption that she will transform into a cat at the prospect of intimacy. Tourneur’s film considers how passion and repression are the twin pillars of sex. It is a strange, bold way of approaching the idea of relationships; making the ways women’s bodies betray them in relation to men explicit in the text.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.