The Cloverfield Paradox represents the nadir of J.J. Abrams’ mystery box

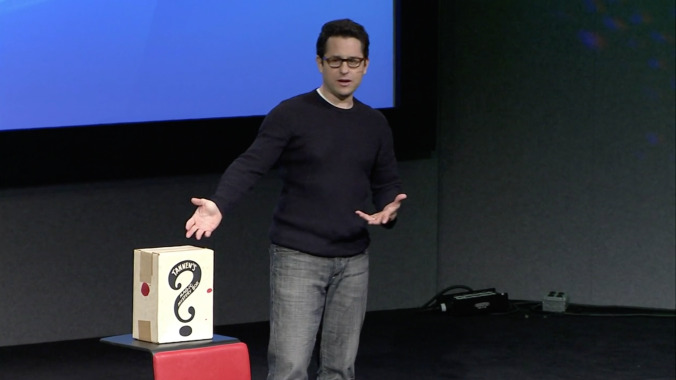

Back in 2007, J.J. Abrams gave a TED Talk in which he discussed his storytelling philosophy and introduced audiences to something he calls “the mystery box.” In addition to being a cheap magic shop gag, the unopened mystery box became a metaphor for the narrative elements Abrams was most passionate about, i.e. infinite possibilities, potential, and open-ended questions. In the follow-up to his recent analysis of the Cloverfield marketing strategy, YouTuber Ryan Hollinger takes a look at how Abrams’ mystery box went from being an intriguing narrative hook to the franchise’s frustrating achilles heel.

According to Hollinger, the main issue with J.J. Abrams’ approach to mystery is that he’s not as concerned with the psychological effect mystery has on characters as he is with the spectacle mystery provides for the audience. The first Cloverfield was essentially a classic monster movie built solely on spectacle, and the lack of coherent answers was an integral part of the found-footage narrative device. The mystery behind what the hell was going on was just as intriguing as the actual visuals on screen.

But by the time Bad Robot got around to making a sequel, the Cloverfield-brand of mystery had become just that: a brand. 10 Cloverfield Lane—originally titled The Cellar—was a perfectly solid, low-budget thriller that would have been swallowed up at the box office had it not been stamped with the Cloverfield name. Unfortunately, that also meant some sort of giant monster/alien sequence had to be tacked on to the film’s third act. The line between spiritual sequel and literal sequel was becoming blurred thanks to Abrams’ mystery box of infinite possibilities.

Anyone who stuck around until the end of Lost knows that a narrative world built on endless questions ultimately ends in frustration, which is what brings us to The Cloverfield Paradox. As Hollinger points out, this was yet another independent property that was given the Cloverfield treatment, though this time well after production was underway. “The originality of its story becomes lost in attempting to unashamedly use a parallel universe deus ex machina to clean the lack of any tangible focus or direction given to these films as a single entity,” he says, adding that the endless possibilities of mystery-box-style writing creates a situation in which there are no concrete rules to the world of your story.

Simply put, a mystery is a great place to start, but not knowing how that mystery resolves (even if you don’t tell your audience) is a problem.

Send Great Job, Internet tips to [email protected]