The ostentatious Gris has got one thing going for it: A damn fine double-jump

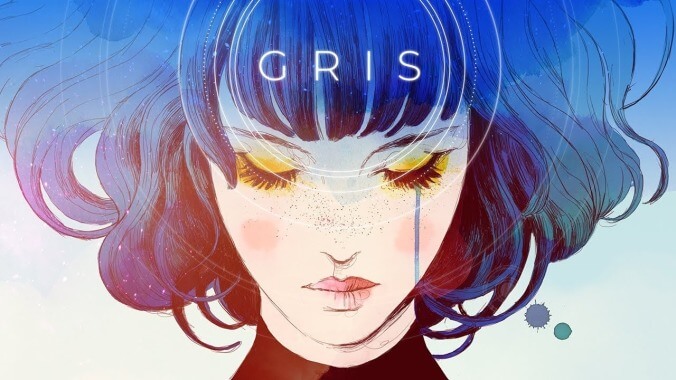

I cannot say that I am entirely sold on Gris, the extremely art-directed game from the Spanish studio Nomada. Credit must be given for the boldness with which it stakes out its visual space, full of fluttering, seemingly hand-drawn animations and big washes of watercolor paint, all arrayed into a surprisingly large fantasy world that seems equally inspired by Moebius and, like, Thirty Seconds To Mars album art. It can be quite beautiful, but it insists upon this beauty, constantly pulling the camera out with a melodramatic swell of strings so you can gaze at yet another expanse of white and yellow and taupe ruins. It’s like an unusually good-looking person at a normal-person bar who is sort of demanding, through sheer extravagance of dress and volume of voice, that they be surrounded by courtiers and attendants and well-wishers the whole time. You want to both look at them and ask the bartender to kick them out.

All of which might seem a little harsh, but there’s a good game underneath all of this self-conscious beauty—a Metroid-lite exploration game, with elegant puzzles and an understated story of personal awakening. (Some of the game’s marketing foregrounds this story, but its actual execution isn’t cloying.) I quite liked some of these light puzzles, which begin at an almost subconscious, spatial level—“where exactly do I go?”—before turning into the more pointed “how the hell do I get that?” variety. It’s a Metroidvania without much backtracking, in other words, taking cues from Aquaria and Ori And The Blind Forest but treating their difficulty and mechanics as a sort of elemental thing, closer to Journey or Abzu.

Gris gets something else really right, too, from all of the games I mentioned: the importance of a sense of propulsion in a friction-free “art” game like this. Your nameless avatar—maybe her name is Gris, I am realizing now? whatever—runs at a finely animated jog, but all of her eventual power-ups prove to be gloriously tactile variations thereupon. The first of these—turning into a big-ass cube—seems to derail momentum, until you realize you can do it mid-air, from extraordinary heights, turning into an anvil that shatters the world’s crumbling stonework. The next of these—last one I’ll spoil—is written in the stars from the game’s outset: a double-jump, the most de rigeur upgrade in the entire Metroidvania pantheon, and yet one executed with loving precision and deceptive power, letting you blast skyward or float for miles to the earth. As with any good double-jump, you immediately find yourself using it constantly, for no reason, soaring happily through the rest of the game and leaping up never-ending staircases two awkward hops at a time. It’s proof positive of the sturdy, mechanical skill of Nomada’s small team; even if Gris is ultimately a misfire, they’ve got a good game in them somewhere.