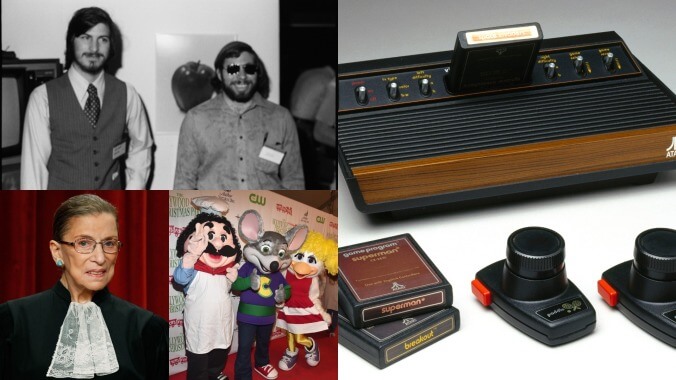

What do Steve Jobs, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Chuck E. Cheese have in common? This early Atari hit

We explore some of Wikipedia’s oddities in our 6,297,990-week series, Wiki Wormhole.

This week’s entry: Breakout

What it’s about: One of the simple-yet-addictive games of the first wave of video games, 1976’s Breakout took the basic mechanics of 1972’s pioneering Pong (in which a paddle slides back and forth and hits a ball), and gave it a twist—instead of hitting the ball to an opponent, it smashes a wall of bricks. That simple concept not only gave the Atari 2600 console one of its first big hits, it set a chain of events in motion that would change the world of computers forever.

Biggest controversy: Breakout’s simplicity made it easy to play, but harder to copyright. Atari’s copyright filing was initially rejected, with the government arguing the game didn’t have enough distinctive graphics or sounds. Atari appealed, and then-appellate court judge Ruth Bader Ginsburg found in Atari’s favor.

Strangest fact: Most games of the 1970s would simply repeat a handful of screens, sometimes increasing the speed or difficulty with each iteration. But Breakout simply stopped after the second screen was cleared. You could keep bouncing the ball around an empty screen once all the bricks were gone, and once you got tired of that, you could let the ball go and lose on purpose, or restart the game. As such, the highest possible score was 896, as each screen was worth 448 points. But players discovered a loophole in the game: If you played in two-player mode, and player one completed the first screen with their last ball, and immediately died once the screen was clear, player one’s score would carry over to player two. If player two could complete two screens without losing a ball, they’d get a score of 1344.

Thing we were happiest to learn: Breakout’s development team went on to bigger and better things. Atari founder Nolan Bushnell came up with the general concept for the game, but he assigned its development to one of his young programmers, Steve Jobs. Jobs roped in his friend, a hardward whiz named Steve Wozniak. Wozniak was employed by Hewlett-Packard at the time, and couldn’t work on an Atari project outright—so Jobs promised to give Wozniak half his fee for the game in exchange for his help.

Wozniak came into Atari after hours for four consecutive nights, after which the duo had created what would become a hit game. But Wozniak saw something bigger. He was a member of the Homebrew Computer Club, whose members would built simple computers. Having successfully designed the hardware for Breakout, he set his sights on something bigger: a personal computer, one that wouldn’t just play games like the Atari 2600, but would be able to run Integer BASIC, the programming language Wozniak was also developing. The result was the Apple I, a limited-edition, hand-made home computer Wozniak and Jobs sold out of Jobs’ garage the year after collaborating on Breakout. The year after that, Wozniak refined his ideas and built the Apple II, still building on ideas from Breakout like the color graphics and sound he had developed for the game.

Wozniak rightly deserves the lion’s share of credit for inventing the personal computer, but it’s not clear that it would have been the world-changing invention it became without Jobs’ marketing vision. Based on a quote in the Wikipedia article, it sounds like Wozniak invented the personal computer so he could show it off to his friends—he cloned Breakout in BASIC, to run on the Apple II, and said it, “was the most satisfying day of my life,” when he was able to demonstrate the game. (Apple later marketed the knockoff as Brick Out.)

Thing we were unhappiest to learn: Jobs couldn’t resist screwing over his friend, and that move could’ve doomed one of the most important partnerships of the 20th century. Bushnell was aware of Jobs’ friendship with Wozniak, and Wozniak’s hardware savvy. Atari games were getting more complex, and using more transistor-transistor logic chips, which were expensive to produce. But Bushnell knew Wozniak had designed a version of Pong that used 30 chips—a typical Atari game used 150 to 170—so he was hoping Jobs would lean on his friend for help.

To further incentivize Jobs, Bushnell offered a payment of $750 for the game, but also a bonus for every chip fewer than 50 the final design used. Jobs and Wozniak delivered a game that ran on 44 chips, claiming they had a design for 42, but “were so tired [they] couldn’t cut it down.” Their design was actually too good—so compact that it would’ve been difficult to manufacture, so Atari’s own hardware designers re-created Wozniak’s design and used approximately 100 chips to do it.

Nonetheless, Bushnell kept his promise, giving Jobs a $5,000 bonus for the 44-chip design. Except he never told Wozniak. Jobs pocketed the $5,000, and split the original $750 fee with is friend. Wozniak didn’t find out until years later, still believing in 1984 that they “only got 700 bucks.” By the time he learned the truth, Apple had made both men millionaires, but had he discovered Jobs’ duplicity at the time, their partnership would likely have splintered, and who knows how many years would have passed before someone else brought the first home computer to market.

Also noteworthy: The Atari 2600 console attached to your TV, so its games were naturally in color. But for the stand-up arcade version of Breakout, a black-and-white screen was cheaper, so Atari put strips of cellophane over the screen to make it look like the rows of bricks were in color. The game was still a hit—there were 11,000 Breakout cabinets made, and Atari sold 1,650,336 copies for the 2600. (The arcade version alone brought in $11 million, making even Jobs’ $5,000 bonus seem chintzy by comparison)

Best link to elsewhere on Wikipedia: While he’s a minor player in this story, Nolan Bushnell is a fascinating figure in his own right, and a giant in the early world of computing. He had dreams of working for Disney, but when they didn’t hire him after college, he got a job as an electrical engineer and met Ted Dabney, who would play the Wozniak to Bushnell’s Jobs. Dabney took Bushnell to the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Laboratory to show him Spacewar!, the first computer game to be installed on more than one computer. Bushnell immediately saw the potential, and convinced Dabney to create a coin-operated Spacewar! to sell to arcades. They formed a company called Syzygy, and their Spacewar! knockoff, Computer Space, was the first arcade video game, and the first computer game available to the general public.

Astonishingly, the two discovered the name Syzygy was already taken, so they renamed their company Atari. Their next project was a coin-op video tennis game, which they named Pong. Pong was a huge hit, although Bushnell used his proceeds to buy out Dabney, who was complaining about being pushed aside by his partner. Dabney went on to develop a home version of Pong. That was a huge hit, and Atari built on its success with the 2600, which could play multiple games.

While Bushnell did hire Jobs and Wozniak for Breakout, afterwards he turned down their design for the Apple I, which they had hoped Atari would manufacture. He also declined an offer to be an initial investor in Apple, Inc., later saying, “It’s kind of fun to think about that, when I’m not crying.” Instead, he put his money into a pet project: a combination pizza parlor and arcade, a venue that could show off Atari’s arcade games in a more family-friendly environment than the bars that usually stocked the company’s products. He named the place Pizza Time Theatre, but looking to add attractions, he drafted an animatronic band modeled on Disneyland’s Country Bear Jamboree. He planned to rename the restaurant Coyote Pizza, after the coyote main character, but when the costume arrived, it turned out to be a rodent, prompting a new name: Chuck E. Cheese.

Having built two thriving companies, Bushnell has spent the years since founding several more, including one of the earliest tech business incubators, Catalyst Technologies Venture Capital Group. (One of Catalyst’s investments: Etak, whose digitized maps laid the groundwork for modern navigation systems.) There was also talk in 2008 of a biopic, with Leonardo DiCaprio producing and possibly starring, but it never materialized.

Further Down the Wormhole: From its humble beginnings selling Wozniak’s home-made computer out of Jobs’ garage, Apple, Inc. has become the world’s most valuable company. While it has taken flak for its environmental footprint, Tim Cook, Jobs’ successor as Apple CEO, has pushed the company to be far greener. 93% of their global operations run on renewable energy, and the company has protected 36,000 acres of forest in North Carolina and Maine, with plans to work with the World Wildlife Fund to preserve a million acres of forest in China.

Maine, is of course largely forest, occasionally broken up by the small towns where all of Stephen King’s stories take place. The state is rural enough that it only has two airports large enough to handle passenger jets, Portland International Jetport, and Bangor International Airport. In the early days of air travel, Bangor was a key refueling stop for planes making a transatlantic crossing. And in 1977, it momentarily delighted the nation when a German tourist landed there and mistook Bangor for San Francisco. We’ll hear the story of misbegotten traveller Erwin Kreuz next week.