When it comes to interactive nightmares, you just can't beat the (in)human touch

Every Friday, A.V. Club staffers kick off our weekly open thread for the discussion of gaming plans and recent gaming glories, but of course, the real action is down in the comments, where we invite you to answer our eternal question: What Are You Playing This Weekend?

Horror has done pretty well by video games. It took a few console generations, but by the time the PlayStation era came around, developers had the tools available to create decent facsimiles of several flavors of the spooky movie genre, heralding the dawn of survival horror as a whole. (And yes, of course there are dozens of earlier games that walked this ground so that Resident Evil’s window-smashing dogs might run; nobody’s engaging in Sweet Home or The Lurking Horror erasure here.) But despite its spread deep into the heart of the machine, video game horror has also remained a thoroughly curated affair. Other genres might benefit from the rise of procedural generation in gaming, allowing algorithms to churn out levels, enemy placements, and other details once the sole province of a human hand. But horror requires an author, a guiding touch from a human being who understands the steady cultivation of fear. Right?

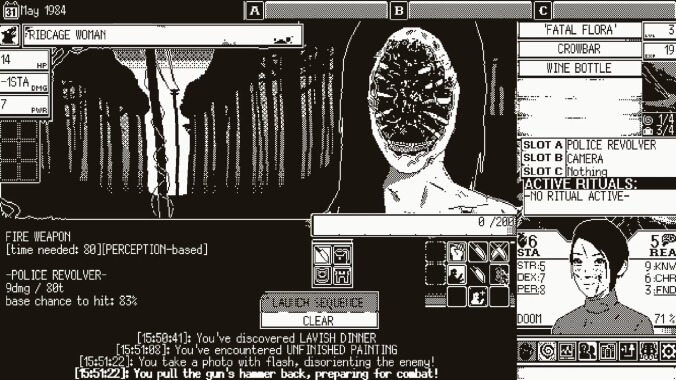

It’s a question raised to gut-lurching effect by new computer shocker World Of Horror, which debuted recently (and to heavy acclaim) on Early Access on Steam. Heavily influenced by the art of Japanese master of the queasy and off-kilter Junji Ito, the game sets you up as a teenager investigating the strange occurrences in a quiet seaside town, then knocks you back down by revealing that those mysteries are massively, hideously beyond your ken. Gorgeously monochromatic, immaculately soundtracked, and stylistically obtuse, the game is an aesthetic triumph. Whether you’re being confronted by a shambling and grinning corpse with murder on its non-existent mind, or just staring in a mirror and watching your reflection distort and corrupt itself of its own accord, the game is an overstuffed buffet of creepy delights, all loaded into a loose framework of cases doled out in semi-random order by the computer.

And it’s not scary. Like, at all.

Unnerving, sure. Grotesque, wonderfully so. But there’s no dread, no rising sense of lurking awfulness, no matter how hard the game’s rising Doom meter might try to convince you otherwise. And it’s all due to the random nature of the game’s event system, which ends up feeling like someone applied William Burroughs’ cut-up technique to a stack of Lovecraft novels and horror manga and then mounted their best efforts at turning the resulting patched-together corpse into a story. The individual moments can land well enough—and those cases that do offer more “authored” content, like the one that sends you to a vigil in an abandoned mansion where you’re not allowed to leave until it’s all resolved, stand out—but two dozen weird or upsetting incidents do not a good horror story make. The writing of individual event cards is great, and little touches—like a “bite” affliction that constantly threatens to become something else—are legitimately chilling. But it’s enough to make you bemoan the fact that developer Panstasz didn’t take this amazing art and love for the form and apply it to a fully designed experience instead. A little bit of randomness and chaos is creepy. A lot of it is just another Junji Ito Twitter feed.

Is procedural horror possible? It’s been tried before—in fact, World Of Horror plays a lot like Ben “Yahtzee” Croshaw’s similarly assembled The Consuming Shadow, released back in 2015. Back when they still made games, Valve’s Left 4 Dead series did amazing work with an A.I. director designed to measure—and exploit—player tension (even if those games are more rightly action titles than outright horror). But the best example that comes to mind is really just authored content of a different sort: Illfonic’s fascinatingly unsuccessful Friday The 13th: The Game, which set one player, as Jason Voorhees, to hunt the rest across Camp Crystal Lake. Ninety percent of the time, the game was a buggy, troll-prone mess. That last 10 percent, though—when the Jason player committed to their role as an implacable, lurking presence in the dark—it managed to generate scares without its developers having to do anything besides keep the servers on.

It just goes to show: There might be a disembodied, scab-ridden hand slowly creeping up your chair at this very moment, eager to drag you into a nightmare of sorrow and unreality—but that plunge into the dark still requires a human touch.