Why is it so hard to make a good comedy game?

As with so many troublesome aspects of the creative process, comedy is something that video games—currently in the “angry teenager punching walls” stage of its development as an artistic medium—is clumsily fumbling with. There have always been reliable sources for legitimately funny video games: Douglas Adams penned absurdist odysseys like 1987’s text-only change-of-address-form simulator Bureaucracy, and LucasArts made a name for itself in the early ’90s with a now-legendary series of cartoon-esque adventures games that included Monkey Island, Sam & Max Hit The Road, and Day Of The Tentacle. But as funny as these games were, they were also outliers, locked away, with a few rare exceptions, in the niche world of computer gaming. When Monkey Island’s Guybrush Threepwood was wandering around Mêlée Island and telling rival pirates that they fight like a cow, the biggest gaming company in the world was busting out “Our princess is in another castle!” callbacks as its earliest stabs at written humor.

It’s a problem that’s only persisted and intensified over the last three (highly lucrative) decades of growth and expansion in gaming, plaguing an industry in which a written script is, as often as not, considered a late-development afterthought. The biggest difference is that there are far more games trying to tell jokes in the 21st century, whether it’s the running distillation of Reddit memes that powers the Borderlands franchise, “funny” lines sprinkled into otherwise boring games, or titles that were actually developed as comedic projects.

Take the nearly forgotten Xbox 360-era shooter Eat Lead: The Return Of Matt Hazard for instance. The winner of the 2009 Spike Video Game Award for Best Comedy Game (it was the only nominee that year) is a perfect example of what happens when everyone involved in the creative process just shrugs and tells themselves “Hey, we can write a funny video game, right?” Credit where it’s due: The premise of Eat Lead is ingenious, “resurrecting” a fictional ’90s action hero and forcing him to play through the whole invented history of his namesake franchise. With a lead character voiced by Will Arnett, and multiple genres’ worth of material to plow through, it should have been an easy win—if any of the writing had actually been, well, funny. It takes Eat Lead approximately 30 seconds to tell its first dick joke, which should let you know how well those efforts went.

Comedy writing is difficult, specialized work, even when the writer is operating under ideal conditions. Film affords a greater amount of control over aspects of story- and joke-telling like timing and pace. In gaming, where forward motion, camera angles, and so much more are frequently ceded to the whims of the players, it becomes exponentially harder—especially when you’re working from some pretty lousy role models to begin with. We’re not just talking about the legacy of truly dire full motion video titles like Plumbers Don’t Wear Ties, the Rob Schneider-drenched A Fork In The Tale, or the John-Goodman-needed-to-make-a-car-payment parody Pyst, either. (The heyday of FMV was not a good time for funny games, no matter who had control of the camera.) The opening to Eat Lead blatantly positions itself as an homage to 3D Realms’ Duke Nukem, which had earned a reputation as a franchise with a sense of humor, mostly by ripping off old John Carpenter and Bruce Campbell quotes, tossing out numerous references to cheerful self-pleasure, and allowing players to toss dollar bills at pixelated strippers.

Hazard managed to beat his inspiration to the punch when it came to storming the modern gaming scene. When the long-delayed Duke Nukem Forever arrived in 2011, it was somehow even more hackneyed, creaky, and derivative than a game whose derivativeness was the whole point. Forever seems to have been written with the assumption that anything sufficiently vile said by Duke Nukem, or the lifeless marionettes surrounding him, is automatic comedy gold. The game’s belief that shock and comedy are adequate substitutes for each other comes through clearly in Forever’s most infamous sequence, in which Duke’s girlfriends—loosely based on the Olsen twins, a reference as timely as everything else in the 2011 title—are impregnated by alien invaders, make a joke about promising to “get the weight off,” and then messily die. This is meant to invoke both humor and pathos, as series voice acting veteran Jon St. John growls out a threat to avenge them that carries exactly the same intonation and emotion as he did while mourning a blown-up spaceship in Duke Nukem 3D.

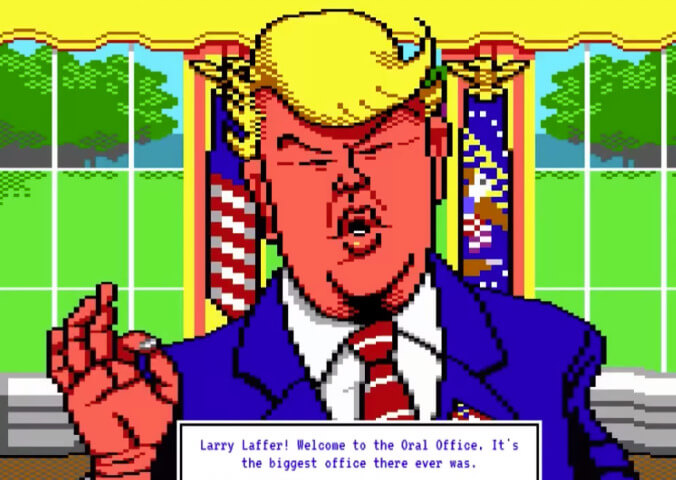

“These lines are funny, because they’re in a Duke Nukem game,” the writers presume, thus finding no outstanding reason to try to make them actually good. Ditto another group of revivalists who probably could have stood to have left a washed-up gaming comedy hero in the grave: The people behind Leisure Suit Larry: Wet Dreams Don’t Dry, the only video game we know of that forces you to look an EGA-styled Donald Trump directly in his beady, squinting eyes while laughing off jokes about sexual assault.

These jokes are offensive and gross. But they’re also lazy. Comedy cannot be an afterthought; it does not simply show up, or get tossed in to a project at the last minute to spice things up. (No matter what certain schools of modern blockbuster screenwriting might suggest.) Writing a funny game means acknowledging the scope of the task you’ve set for yourself, and building the game itself to support that effort. When The Stanley Parable tells its jokes about the nature of video game narratives, they land, not just because of Kevan Brighting’s wonderfully smug narrator voice, but because the entire gameworld has been built in support of them. Asymmetric’s West Of Loathing doesn’t just boast an uproariously funny script—although it does, in fact, boast exactly that. It also uses its built-in mechanics to tell and support its jokes, whether forcing you to walk down a nigh-endless tunnel filled with shaggy-dog jokes, or asking you to trudge, step by step, through the exacting bureaucracy of a literal ghost town. When Guybrush wins a swordfight by out-punning his opponent in The Secret Of Monkey Island, it’s not just the writing, but the action itself that’s charmingly absurd.

Even beyond the written word, comedy in games is a matter of deliberation and thoughtfulness. When a Dark Souls designer places a chest that’s actually a monster that shoves your hapless character into its waiting maw, the game is telling a joke that relies on everything from the animation team, to the player’s own actions, to the expectations set up by the placement of other, non-carnivorous chests. The goofy flopping of the noodle-armed humanoids in games like Gang Beasts and Human: Fall Flat might be generated by the players pressing buttons, but it’s also the product of designers, animators, and programmers tweaking it for optimal comic effect.

In that light, the failures of Matt Hazard aren’t just in telling jokes that aren’t very funny; despite its inspired premise, the world that the designers at Vicious Cycle built to tell those jokes was decidedly rote, too. You can’t just build an unfunny game, then fill it with a million memes, little people, and a crystal pony named Butt Stallion (to pick one particular, egregious franchise wholly at random) and expect brilliance to simply appear. Comedy is an act of creation, and it requires just as much care as coding a physics engine or designing a puzzle. Making good games that are actually funny is difficult, laborious work, and the failure to respect that process is a pretty decent indication of why so many of them have sucked.