The best, worst, and weirdest games from Resident Evil’s 20-year history

Resident Evil has a whole hell of a lot of details to sort through, and not all of them are worth visiting, let alone revisiting

“Itchy. Tasty.” These are the words scrawled on a piece of notebook paper you find in a back room of Resident Evil’s Spencer Mansion. It’s an entirely optional find, just a little piece of color to make Shinji Mikami’s horror game that much more unnerving. Finding evidence of zombies in Resident Evil isn’t scary; they’re everywhere. What’s thrilling about the note—even now, 20 years after the blocky mansion full of scabby animals and inexplicable puzzles made its debut—is that it’s one more vivid detail in a seemingly never-ending tide of them. Resident Evil is specific. Resident Evil is precise. Every facet of the series’ best entries rings distinct.

With two decades of history and more than two dozen games under its umbrella, Resident Evil has a whole hell of a lot of details to sort through, and not all of them are worth visiting, let alone revisiting. Over the years, Capcom’s horror series has been equally grand, insufferable, and inexplicable. Sometimes it’s been all three at once.

Best: Resident Evil 2 (1998)

While Resident Evil referred to itself as “survival horror” from the start, the horror half of that moniker has never been an ideal hook to hang its hat on. Bio Hazard (as the series is known in its native Japan) and its sequels share more with John Carpenter operating The Thing mode than Halloween. They’re thrillers where good people have to deal with the fallout of bad people using weird science to do bad things. Mix in double-doses of soap operatics, unrealistically wielded heavy weaponry, and maze exploration, and you’ve got Resident Evil.

The ’96 original is more iconic at this point—thanks in large part to the excellent 2002 remake—but Resident Evil 2 is the game that most firmly established and excelled at its central formula. Every Resident Evil is in some way about pairing characters together, and Resident Evil 2 is the most successful at creating a meaningful link between its stars. The stories of Leon S. Kennedy and Claire Redfield are slightly different and have to be played back-to-back if you want to find the game’s true ending (and its astounding Huey Lewis-ian butt-rock song). Your second playthrough of RE2 also introduces Tyrant, a constant un-killable threat that became a recurring enemy archetype in later entries and the defining figure of Resident Evil 3: Nemesis.

Resident Evil 2 pulls off the tricky balancing act most sequels struggle with: It echoes its predecessor while also expanding on it, never blowing up to the point that its pre-established identity is sacrificed or playing it so safe that it’s just retreading old ground. (This was a sticking point for series mastermind Shinji Mikami. Resident Evil 2 was almost finished in 1997 when he scrapped the whole thing for being too similar to the original.) Picking up shortly after the first game, the bio-engineered virus that turned the Umbrella Corporation’s employees into shuffling, flesh-eating monsters has come down from the Arklay Mountains and into the fictional American town of Raccoon City. It’s overrun with killer freaks but so isolated that Claire and Leon have no idea what’s happening when they arrive. It’s the perfect set up for a survive, escape, and solve-the-mystery scenario.

A few things elevate Resident Evil 2 over its predecessor as well as many of the games that followed. First is the environment itself. Rather than its blank characters, the settings are the real stars of Resident Evil. Raccoon City extends the scale of the Spencer Mansion without losing the pleasure of its puzzlebox layout. Only a small amount of time is spent on the city’s debris-littered streets. Most of the game takes place in the Raccoon City Police Department, a viper pit that’s as full of bizarre jewel-based door locks as the Spencer Mansion, but is made more unnerving because of how mundane it is. Skinless, eyeless monsters with stabby six-foot tongues might be crawling around rooms with trapdoors, but there’s still a front desk where you can practically smell the receptionist’s stale coffee. The second half of the adventure leads to yet another underground Umbrella research facility, albeit one with far less irksome backtracking. Resident Evil 2’s is a world that feels bigger but doesn’t lose the focus that made the mansion so memorable.

A focus on speedy play also makes the more action-centric Resident Evil 2 even more frenetic. Finish the first scenario in under 150 minutes, and you unlock a rocket launcher with infinite ammunition. The series is mistakenly associated with a scarcity of supplies, but Resident Evil 2 rooted its rhythm in acquiring a steady stream of big guns and the ammunition to use them. This is, after all, a game where you can blow up a giant crocodile’s face by tricking it into chomping on an oxygen tank then shooting it. Resident Evil 4, which rejuvenated the series in 2005 with a shift in presentation and setting, is directly indebted to RE2’s amped up action. Unfortunately as the series went on, its curators failed to realize that, while RE2 sang by broadening its scale and reach, there’s such a thing as expanding too much.

Worst: Resident Evil 6 (2012)

In all the ways Resident Evil 2 is successful, Resident Evil 6 is vomitous. Eichiro Sasaki is credited as directing the 2012 sequel, the last numbered entry in the core series, but it was made by 600 employees spread across of Capcom’s internal studios and contract houses. There are 16 individuals credited as “game designers.” Calling it a chimera doesn’t begin to cover it. Resident Evil 6 is a lumbering monstrosity as malformed and sprawling as the eye-and-tentacle covered bosses that populate it. The infinite monkey theorem is no longer a rhetorical exercise—Resident Evil 6 is the inevitable, very real result.

It’s even difficult to properly describe Resident Evil 6. Rather than two interlocking campaigns that can be completed and replayed in a few short hours, it houses three different 10-hour stories with three pairs of characters, each loosely defined by a different style of action. Leon returns and is teamed with a special agent named Helena in what’s supposed to be a slower, more exploratory story with zombies. Chris and Piers are machine-gun-toting fighters pitted against super soldiers who explode monster moths out of their butts (seriously), while Sherry Birkin and the mysterious Jake Muller are all about awkwardly choreographed fistfights and getting hounded by a giant clawed guy named Ustanak (yet another Nemesis retread). Play through that whole morass, and a fourth story starring corporate super-spy Ada Wong opens up so you can fight more butt moths.

Given the sprawl of styles, characters, and settings at play in RE6, it’s not surprising that the game is devoid of the specificity and incident that makes for the best Resident Evil games. Part of the problem is that it never slows down long enough for anything to sink in—not its action, nor the details of its world. In the span of a couple hours, Leon and Helena are shunted through a college campus, a presidential assassination, a huge series of underground caverns, and a night time plane ride where the pilot is still wearing sunglasses when he’s murdered by a walking, smoking purple pile of breasts. Forget trying to keep up with the story; it’s hard enough to maintain a sense of your immediate surroundings.

Atmosphere is never cultivated, individual facets of the world disappear, and its impossible to get comfortable with how the characters themselves move. Resident Evil 6’s characters are more malleable and acrobatic than at any other point in the series, but they feel soft and ill defined as a result of the expanded controls needing to suit so many different scenarios. There are still memorable sights: In one of the first scenes, when Leon enters a darkened ballroom on Tall Oaks’ college campus, some of the environmental grandeur of the past seeps into the game. But where that room would have hidden some mysterious document or a life-saving tool to break through a locked door you passed 20 minutes back in Code: Veronica or Resident Evil 4, here it’s just a cosmetic facade. There’s nothing grounding the spectacle, and no series of endlessly escalating fights against mutating corporate overlords and monsters can replace what’s lost.

Weirdest: Resident Evil Outbreak (2003)

Part of the reason Resident Evil 6 became such a muddy pile of parts was that Capcom was convinced the only way the series could stay a multi-million selling success was to chase the multiplayer gaming audience. This push started with 2009’s Resident Evil 5, a game born on technology where playing with other people over the internet had finally become ubiquitous. It was also smack in the middle of an era when the skyrocketing cost of developing games on the cutting edge of technology—something the PlayStation’s Resident Evil games were known for—meant having to chase the broadest possible audience. The perception was that multiplayer gaming was the quickest route to that kind of success, thus a more streamlined series of Resident Evil games with a variety of ways to play with other people was born. Deeply specific thriller scenarios weren’t the priority in Resident Evil 6; explosive action set pieces where players could drop in or out at any time were. It’s not an inherently bad idea, but it’s not one suited to Resident Evil.

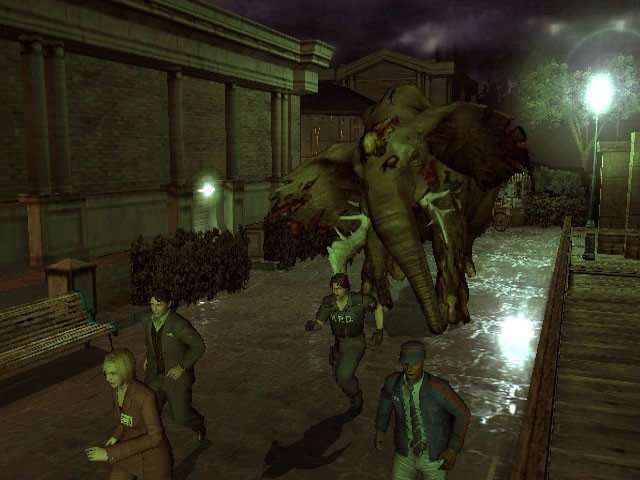

Nearly a decade before he directed that debacle, Eichiro Sasaki actually tried to translate Resident Evil’s winning formula into something people could play together, and the result was the series’ most peculiar digressions. Resident Evil Outbreak for PlayStation 2 is structured similar to the Resident Evil games that had come out before 2003 and even takes place contemporaneously with Resident Evil 2. Selecting one of eight characters, each with a specific ability or item, you’re thrust into the Raccoon City zombie outbreak and stuck in a bar, hospital, or other locale full of oblique puzzles and locked doors. The difference between Outbreak and RE2 is that you have to either control multiple characters at the same time or play with multiple people online to get through it.

The structure is sound on the surface. Other teams working on the series were already toying with how to let you use multiple characters at the same time. Resident Evil 0 put you in control of two survivors—unlike the four characters used at any given time in Outbreak. You could swap items in their limited inventories at will and solve puzzles that required people to be in multiple places, like on opposite ends of a dumbwaiter. Outbreak is also broken into episodes to make it easier for random people to join up online. Not having one seamless world makes it so that even when you find a mysterious new key, the whole crew doesn’t have to trundle halfway across a massive map to use it.

But in practice, the game was awkward. The truncated scenarios lacked the cumulative effect of inhabiting a complex space like the Spencer Mansion or Raccoon City Police Department, leaving it feeling too light. And technology itself wasn’t up to supporting the game. With no easy voice chat option on the PlayStation 2, your only means of communication are pre-programmed phrases (“yes,” “no,” “that way”) and an onscreen keyboard that only works in the pre-game lobby. That’s on top of connection issues and prolonged load times that made it a chore to access an online session, even by 2003 standards.

Despite all those headaches, Outbreak still captured a novel feeling that was at least adjacent to the series’ core strengths. What it lacked in consistent atmosphere and satisfying action, it made up for with an immediate sensation of trying to survive with other people. Since you’re usually paired with another character, Resident Evil is never truly lonely, but it’s always isolating. While you’re enduring its stressful scenarios, you’re not sharing that experience. Resident Evil 5 and 6 define the shared experience purely around combat; you’re not solving problems, you’re just ceaselessly shooting or punching or blowing something up. Outbreak manages to bottle some of that apocalyptic togetherness that makes survivor fantasies so beguiling. We’re all in this together, so pass me that blue key before we figure out what buttons to push under these conspicuous paintings.